John Fernald has a new working paper out at the San Fran Fed on "Productivity and Potential Output Before, During, and After the Great Recession". The main take-away from the paper is that productivity growth started to slow down even before 2008, particularly in industries that produce IT products or are significant users of IT products. Because of this, even in the absence of the Great Recession, we would have seen slower trend growth in GDP.

What Fernald's results imply is that the economy is not as far from its potential GDP as we might think. And the idea that we're way below potential GDP is something lingering underneath a lot of the discussion about economic policy (tapering, stimulus, etc...). Matt Yglesias just had a post noting that while the U.S. is well below it's pre-2007 trend for GDP, Europe is even farther below it's trend. Regardless of the conclusion you want to draw from that regarding policy, the assumption is that the pre-2007 trend is where GDP "should" be.

Back to Fernald's paper. He finds that productivity growth was already declining prior to 2007, and therefore where GDP "should" be is a lot lower than the naive pre-2007 trend line would indicate. This is easier to see in a picture.

The purple dashed line is from the CBO's 2007 projection, and that is essentially just an extrapolation of the trend in GDP from about 1990-2007. Compared to that measure of potential GDP, we are doing very poorly, with actual GDP (the black line) falling nearly $2 trillion short of potential.

Fernald's alternative calculations that take into account the slowdown in productivity growth that started in the mid-2000's suggest a much lower estimate of potential GDP. His estimate (the red line) is a prediction of what GDP would have been without the financial crisis, essentially. It falls well below the CBO 2007 estimate. It suggests that the economy today is only perhaps $400 billion short of potential GDP.

His numbers make a big difference in how you think about policy, if only at the quantitative level. If you're for some kind of further monetary expansion or a new fiscal stimulus, then the size of that boost should be calibrated to a $400 billion shortfall, not a $2 trillion one.

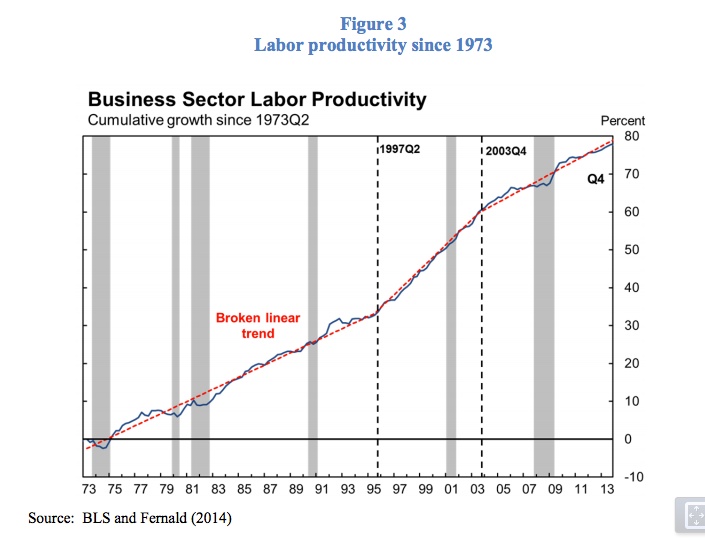

Why does Fernald come up with lower numbers for potential output than the naive forecast in 2007? Without going into the nitty-gritty, he looks at productivity growth (think output per hour) and finds that around 2003Q4, it stops growing as quickly as it did from 1995-2003. What Fernald chalks this up to is the exhaustion of the IT productivity boost. At the time, people thought that the IT revolution might have permanently raised labor productivity growth rates It appears to rather have had a "level effect" - we had a boost in the level of labor productivity, but now it will continue to grow at the normal rate. Again, this is easier to see in pictures, courtesy of Fernald's paper.

You can see that the 1995-2003 period is exceptional in having high labor productivity growth, and that since 2003 we've had growth in labor productivity at about the same rate as 1973-95. Anyone who uses the 1995-2003 period to extrapolate labor productivity growth (like the CBO was implicitly doing in 2007) would overestimate potential output.

This isn't to say that the CBO or anyone else was being lazy or duplicitous. In 2007, if you looked at the data on labor productivity, there would not be enough evidence to suggest that growth in labor productivity had fallen. The data from 1995-2007 would not be enough to tell you if we had experienced a "level effect" from IT that led to a temporary boost to growth rates, or a "growth effect" from IT that had permanently raised growth rates. You can only tell the difference now because we see the slowdown in productivity growth, so in retrospect it must have been a "level effect".

Regardless, Fernald's paper suggests that the scope of the Great Recession is less "Great" than previous estimates would lead you to believe. And given that the trend growth rate in labor productivity is driven primarily by technological innovation, then boosting that growth rate means hoping that someone will invent a new technology that has a transformative power similar to IT.