In response to my recent post on geography/institutions, Thornton Hall posted some comments that led us to go back and forth regarding whether pre-historic/pre-agricultural humans led "long, happy lives" (Hall) or relatively short, dismal lives (me). Yes, this is tangential to the whole geography/institutions thing. It's the internet, what do you want?

Hall pointed me towards several sources of evidence regarding longevity among hunter-gatherers to support his contention that these humans lived a relatively long time (70-ish years). The main source is a paper by Gurven and Kaplan (2007, direct link here) that as it turns out I had hiding on my hard drive anyway.

Gurven and Kaplan (GK) survey the collected evidence on life expectancies on early hunter-gatherers (much of which is based on reviews of current indigenous populations of h-g's like the !Kung). I don't have any reason to dispute the data presented by GK, as I'm not an anthropologist, nor have I read sufficiently in this literature to have any opinion on the sources. My response to Hall's claims regarding the "long, happy lives" of pre-historic hunter-gatherers is based entirely on how that evidence is interpreted.

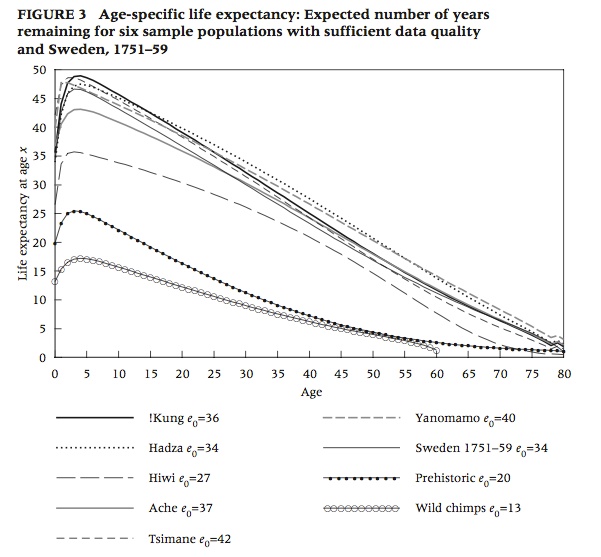

Let's take figure 3 from the GK survey. This shows age-specific life-expectancies for different populations of hunter-gatherers, a hypothetical pre-historic population, and a population of wild chimps. What do we see?

First, life expectancy at birth is very low. These are the e_0 terms shown below the graph itself. This is what you typically think of when you hear "life expectancy" - how many years do we expect a newborn to live? This ranges as low as 27 for the Hiwi, as high as 42 for the Tsimane, but the inferred value for pre-historic populations is only 20. A newborn in a pre-historic society would - on average - live about 20 years.

This is mainly due to very severe infant and child mortality. Pre-historic babies were very likely to die before their first birthday, and making it to 5 years old is unlikely. But, conditional on making it to 5, life-spans could be quite long. So in the figure, you see that life expectancy at age 5 is almost 50 for some societies (so they would life to roughly 55) and 25 for the prehistoric society (so the 5-year old would life to 30).

Similarly, if you make it to 20 years old, you could expect to live another 40 years (so you'd be 60) in many of these populations, and another 20 years (so you'd be 40) in the hypothetical prehistoric society. Let's just focus on the relatively high expectancies for the moment. These life expectancies tell us that a very lucky few hunter-gatherers will live long, happy lives. If you can survive to 20, you can expect to live to 60. If you can make it to 30, you can expect to live to about 70.

My claim that life is short for hunter-gatherers is based on the fact that a huge swath of the population dies by the age of 5. If I ignore them, then sure, average life expectancy is high. But that is like saying average wages in the U.S. are really high if I ignore people who are poor.

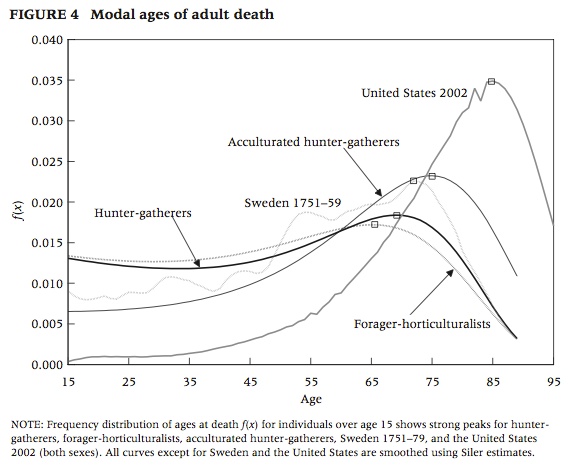

Second, the modal age of death has essentially no information in it. The GK survey, in their figure 4, shows the proportion of all deaths occurring at each age. The dark line is for hunter-gatherers, and it has a modal age of death (the highest point on the curve) of about 70 years.

This does not mean that most people die at age 70. If you look at the y-axis, you'll see that it implies only about 1.6% of all deaths are at age 70. GK refer to this, and note that even with a model age of death of 70, roughly two-thirds of all deaths in the hunter-gatherer society will occur before age 70. Look at the distribution of deaths for the U.S. in 2002 in the same figure. See how the proportion of deaths at ages 15-35 is almost zero. Deaths do not really start to ramp up in the U.S. until age 55 or 60. For hunter-gatherers, there is a consistent chance of dying of about 1.2-1.5% from age 15 to age 65. You are far more likely to die at an age less than 65 in a hunter-gatherer society than you are in the U.S. today.

A last point on this figure is that it refers to ages of death, conditional on reaching age 15, which goes back to my first point. If you only look at the select population of individuals who make it past infant and child mortality, then yes they have the potential to live long periods of time. But that is ignoring the fact that a big chunk of the population will die by the time they are 15.

Final point, which refers to the "happy" part of "happy, long live". I have no idea how happy these hunter-gatherers really were. It may have been a joyous life for them, perhaps far happier than we are today. I have no way of telling you otherwise.

But let me suggest two negatives that the early hunter-gatherers would have to overcome on their way to bliss. One, they had to witness a brutal rate of infant and child mortality. Every time they had a child, the likely outcome was that this child would be dead within 1 year. If it made it 1 year old, then there's a slim chance the kid makes it to 5. You would have buried more kids than you ever saw married off. Oh, and let's not forget that those kids led unhappy lives, dying early, likely from some kind of infectious disease.

Two, according to table 5 from the GK paper, 17% of all deaths for those under 60 were from violence. A similar 17% of deaths for those under 15 were from violence, either homicide or warfare. Close to one-in-five deaths occurred on the end of a spear, knife, arrow, or whatever weapon was at hand. One in five. For comparison, in the U.S. in 2010 (p. 11) only 0.4%, or 1 in 250, deaths are from homicide.

So I don't buy that hunter-gatherers had it made compared to modern people. They died at astonishing rates at early ages, and a massive fraction of those deaths were through violence. Hobbes may have been wrong about life being "solitary", as my guess is that you stuck as close as possible to your trusted family network, but "poor, nasty, brutish, and short" is a good first approximation.