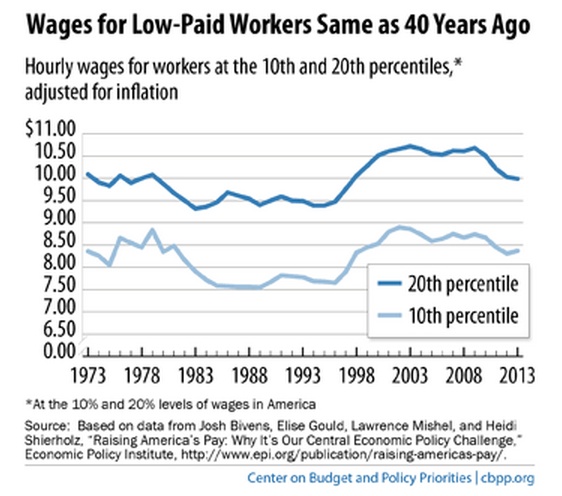

A really common thread running through the comments I've gotten on the blog involve the replacement of labor. This is tied into the question of the impact of robots/IT on labor market outcomes, and the stagnation of wages for lots of laborers. An intuition that a lot of people have is that robots are going to "replace" people, and this will mean that wages fall and more and more of output gets paid to the owners of the robots. Just today, I saw this figure (h/t to Brad DeLong) from the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities which shows wages for the 10th and 20th percentile workers in the U.S. being stagnant over the last 40 years.

The possible counter-arguments to this are that even with robots, we'll just find new uses for human labor, and/or that robots will relieve us of the burden of working. We'll enjoy high living standards without having to work at it, so why worry?

I'll admit that my usual reaction is the "but we will just find new kinds of jobs for people" type. Even though capital goods like tractors and combines replaced a lot of human labor in agriculture, we now employ people in other industries, for example. But this assumes that labor is somehow still relevant somewhere in the economy, and maybe that isn't true. So what does "factor-eliminating" technological change look like? As luck would have it, there's a paper by Pietro Peretto and John Seater called .... "Factor-eliminating Technical Change". Peretto and Seater focus on the dynamic implications of the model for endogenous growth, and whether factor-eliminating change can produce sustained growth in output per worker. They find that it can under certain circumstances. But the model they set is also a really useful tool for thinking about what the arrival of robots (or further IT innovations in general) may imply for wages and income distribution.

I'm going to ignore the dynamics that Peretto and Seater work through, and focus only on the firm-level decision they describe.

****If you want to skip technical stuff - jump down to the bottom of the post for the punchline****

Firms have a whole menu of available production functions to choose from. The firm-level functions all have the same structure, ${Y = A X^{\alpha}Z^{1-\alpha}}$, and vary only in their value of ${\alpha \in (0,\overline{\alpha})}$. ${X}$ and ${Z}$ are different factors of production (I'll be more specific about how to interpret these later on). ${A}$ is a measure of total factor productivity.

The idea of having different production functions to choose from isn't necessarily new, but the novelty comes when Peretto/Seater allow the firm to use more than one of those production functions at once. A firm that has some amount of ${X}$ and ${Z}$ available will choose to do what? It depends on the amount of ${X}$ versus the amount of ${Z}$ they have. If ${X}$ is really big compared to ${Z}$, then it makes sense to only use the maximum ${\overline{\alpha}}$ technology, so ${Y = A X^{\overline{\alpha}}Z^{1-\overline{\alpha}}}$. This makes some sense. If you have lots of some factor ${X}$, then it only makes sense to use a technology that uses this factor really intensely - ${\overline{\alpha}}$.

On the other hand, if you have a lot of ${Z}$ compared to ${X}$, then what do you do? You do the opposite - kind of. With a lot of ${Z}$, you want to use a technology that uses this factor intensely, meaning the technology with ${\alpha=0}$. But, if you use only that technology, then your ${X}$ sits idle, useless. So you'll run a ${X}$-intense plant as well, and that requires a little of the ${Z}$ factor to operate. So you'll use two kinds of plants at once - a ${Z}$ intense one and a ${X}$ intense one. You can see their paper for derivations, but in the end the production function when you have lots of ${Z}$ is

$$ Y = A \left(Z + \beta X\right) $$

where ${\beta}$ is a slurry of terms involving ${\overline{\alpha}}$. What Peretto and Seater show is that over time, if firms can invest in higher levels of ${\overline{\alpha}}$, then by necessity it will be the case that we have "lots" of ${Z}$ compared to little ${X}$, and we use this production function.

What's so special about this production function? It's linear in ${Z}$ and ${X}$, so their marginal products do not decline as you use more of them. More importantly, their marginal products do not rise as you acquire more of the other input. That is, the marginal product of ${Z}$ is exactly ${A}$, no matter how much ${X}$ we have.

What does this possibly have to do with robots, stagnant wages, and the labor market? Let ${Z}$ represent labor inputs, and ${X}$ represent capital inputs. This linear production function means that as we acquire more capital (${X}$), this has no effect on the marginal product of labor (${Z}$). If we have something resembling a competitive market for labor, then this implies that wages will be constant even as we acquire more capital.

That's a big departure from the typical concept we have of production functions and wages. The typical model is more like Peretto and Seater's case where ${X}$ is really big, and ${Y = A X^{\overline{\alpha}}Z^{1-\overline{\alpha}}}$, a typical Cobb-Douglas. What's true here is that as we get more ${X}$, the marginal product of ${Z}$ goes up. In other words, if we acquire more capital, then wages should rise as workers get more productive.

The Peretto/Seater setting says that, at some point, technology will progress to the point that wages stop rising with the capital stock. Wages can still go up with general total factor productivity, ${A}$, sure, but just acquiring new capital will no longer raise wages.

While wages are stagnant, this doesn't mean that output per worker is stagnant. Labor productivity (${Y/Z}$) in this setting is

$$ \frac{Y}{Z} = A \left(1 + \beta \frac{X}{Z}\right). $$

If capital per worker (${X/Z}$) is rising, then so is output per worker. But wages will remain constant. This implies that labor's share of output is falling, as

$$ \frac{wZ}{Y} = \frac{AZ}{A \left(Z + \beta X\right)} = \frac{Z}{\left(Z + \beta X\right)} = \frac{1}{1 + \beta X/Z}. $$

With the ability to use multiple types of technologies, as capital is acquired labor's share of output falls.

Okay, this Peretto/Seater model gives us an explanation for stagnant wages and a declining labor share in output. Why did I present this using ${X}$ for capital and ${Z}$ for labor, not their traditional ${K}$ and ${L}$? This is mainly because the definition of what counts as "labor", and what counts as "capital", are not fixed. "Capital" might include human as well as physical capital, and so "labor" might mean just unskilled labor. And we definitely see that unskilled labor's wage is stagnant, while college-educated wages have tended to rise.

***** Jump back in here if you skipped the technical stuff *****

The real point here is that whether technological change is good for labor or not depends on whether labor and capital (i.e. robots) are complements or substitutes. If they are complements (as in traditional conceptions of production functions), then adding robots will raise wages, and won't necessarily lower labor's share of output. If they are substistutes then adding robots will not raise wages, and will almost certainly lower labor's share of output. The factor-eliminating model from Peretto and Seater says that firms will always invest in more capital-intense production functions and that this will inevitably make labor and capital substitutes. We happen to live in the period of time in which this shift to being substitutes is taking place. Or one could argue that it already has taken place, as we see those stagnant wages for unskilled workers, at least, from 1980 onwards.

What we should do about this is a different question. There is no equivalent mechanism or incentive here that would drive firms to make labor and capital complements again. From the firms perspective, having labor and capital as complements limits their flexibility, because they then depend on the other. They'd rather have the marginal product of robots and people independent of one other. So once we reach the robot stage of production, we're going to stay there, absent a policy that actively prohibits certain types of production. The only way to raise labor's share of output once we get the robots is through straight redistribution from robot owners to workers.

Note that this doesn't mean that labor's real wage is falling. They still have jobs, and their wages can still rise if there is total factor productivity change. But that won't change the share of output that labor earns. I guess a big question is whether the increases in real wages from total factor productivity growth are sufficient to keep workers from grumbling about the smaller share of output that they earn.

I for one welcome....you know the rest.