New paper out by Holger Strulik and Carl-Johan Dalgaard (who I predict is at this moment taking a smoke break). The paper looks at the reversal of the latitude/income relationship over history, and propose a physiological reason for it.

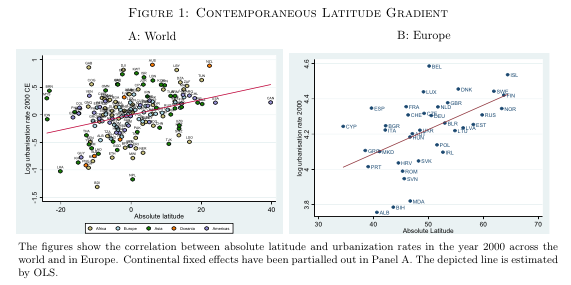

For starters, if you are familiar at all with basic development statistics, then you probably know that latitude and income per capita are positively correlated. The farther away from the equator you get (higher latitude) the richer you get. This works going north or south. South Africa is richer than Nigeria, for example, and Chile is richer than Ecuador. Dalgaard and Strulik have a nice graph showing this relationship holds not only for all countries, but also within Europe.

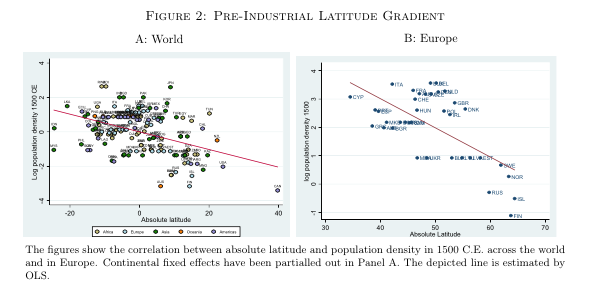

The first really interesting fact in the paper is that this gradient reverses if you look at pre-Industrial Revolution data. For 1500 CE, there is a negative relationship, and countries that are closer to the equator are richer. Again, this also holds within Europe. I had some vague concept that it probably reversed in the whole sample, but the within Europe evidence is really fascinating.

Around 1500, the Mediterranean countries in Europe were better off compared to their Northern neighbors. An aside: Were the Greeks and Italians of 1500 tsk-tsk-ing their profligate Teutonic cousins for their lazy attitudes and lack of robust economic institutions? Discuss.

Anyway, the latitude/income reversal, and the fact that it holds up within Europe, are both by themselves the kinds of stylized facts that you should cram into your head when thinking about comparative development.

But given that you have crammed that information in there, you probably have several questions. (1) Why are hot places rich in 1500, and cold places poor? (2) What changed to make the cold places rich today?

Dalgaard and Strulik take a swipe at these questions, focusing on the physiology involved in hot and cold places. There thesis rests on "Bergmann's Rule", which is a biological regularity noted in 1847. Bergmann's rule states that average body mass of organisms rises as they get farther from the equator. This holds for people as well as animals. People generally have higher body mass farther from the equator (and no, that's not just because of Wisconsin. I kid. Sort of.).

Why does Bergmann's rule hold? Surface area to mass ratios. Big people have lower surface area to mass ratios, so they are more thermally efficient in cold climates. Thus the optimal body type for high, cold, latitudes is large, while for places closer to the equator small body types are optimal to maximize surface area to mass in order to radiate heat.

Now, large bodies have an additional feature. They require a lot of fuel (food), in particular for mothers when pregnant. Big women having big babies means using a lot of food. Thus people in cold latitudes were able to have fewer babies, given a supply of food, than their peers in equatorial regions. So we have bigger populations in equatorial regions and smaller ones in cold latitudes prior to the IR. Big populations mean more innovation in almost any type of growth model you write down, so equatorial regions had more innovation during the pre-IR era, and hence were richer.

But, eventually even the cold latitudes are going to innovate far enough to get the point of inventing technologies that rely on human capital. And the cold climate physiology gives them a natural tendency to favor quality over quantity of kids. Thus families in higher latitudes are going to more easily adopt the human capital using technology. This then starts a feedback effect, where by having a few, high-education kids means they can use the human-capital technology. Which raises income per capita. Which leads to further investment in kids at the expense of family size, and cold latitudes enter the Demographic Transition ahead of equatorial regions.

The reversal is inevitable in their model, given the initial physiological difference between latitudes. The physiological story is also consistent with differences in marriage patterns and child birth patterns between Europe and much of Asia in the pre-IR era.

They use Europe as an example, and how the latitude/income relationship holds today. But it holds in the U.S. as well. Is the income per capita of states in the U.S. consistent with the implied physiological differences between different areas of Europe, Africa, or Latin America due to population composition?

This paper predicts a reversal, but this reversal has to happen "just so" to avoid becoming a-historical. That is, the reversal has to happen just before the equatorial countries (China, India, various iterations of Islamic empires) become sufficiently rich to colonize Europe, snuffing out their development. This leaves Europe to effect the reversal, and go out to colonize the rest of the world. Did Europe get lucky here, or is there some reason that those places don't become colonizers? Luck might be the answer, as you've got plenty of close-run things in European history [the Mongols turning back, Lepanto, Vienna].

The last thing that comes to mind here is that for this physiological difference to have such persistent effects, the family patterns it determines must become either (a) genetically rooted into populations or (b) some deeply ingrained in culture as to be permanent. Fertility behavior is mutable. For it to continue to be a reason for lack of development in equatorial regions you need some strong force keeping people locked into the "bad" preference for lots of kids. What is that force?