Brad DeLong posted about the recent paper by Pritchett and Summers (PS) on "Asiaphoria" and mean-reversion in growth rates. PS found several things:

- Growth rates are not persistent. The growth rate over the last 10 years has very little information about the growth rate over the next 10 years. Growth rates "regress to the mean" as PS say.

- Growth in developing countries tends to take place in bursts of growth and bursts of stagnation. This is different from rich countries where growth variation tends to consist of mild variation around a trend rate.

- There is no reason to believe that rapidly growing economies today (China and India) will necessarily continue to grow rapidly.

Brad's response is to take their evidence as a fundamental challenge to the standard Solow model explanation for why growth rates differ.

Lant Pritchett and Larry Summers are now trying to blow this up: to say that just as the neoclassical aggregate production function is a very bad guide to understanding the business cycle, as the generation-old failure of RBC models tells us, so the neoclassical aggregate production function and the Solow growth model built on top of it is a bad guide to issues of growth and development as well.

This is an overreaction. The mean-reversion and "bursts" that PS find are perfectly consistent with a Solow model including shocks.

Let's start with the finding that regressing decadal growth rates on prior-decadal growth rates gives you a coefficient of something like 0.2-0.3. PS call this mean-reversion. I think it's an artifact of convergence. Let's imagine an economy that is following the Solow model precisely. It is very poor in 1960, and growth from 1960-1970 is about 10% per year. By 1970 it is much better off, and so growth from 1970-1980 slows to 5% per year. By 1980 this has gotten the country to steady state, so from 1980-1990 it grows at 2% per year. From 1990-2000 it is still at steady state, so grows at 2% a year again.

Now regress decadal growth rates (5,2,2) on prior-decade growth rates (10,5,2). What do you get? A line with a slope of about 0.397. Why? Because growth rates slow down as you approach steady state. Play with the numbers a little and you can make the slope 0.3 if you want to. The point is that convergence will generate just such a pattern in growth rates.

What about the unpredictability of growth rates? PS find that the correlation of growth rates across periods is very low. This is more problematic for convergence, on the face of it. If convergence is true, then growth rates across decades should be tightly correlated. In other words, even if the slope of the toy regression I ran above is less than one, the R-squared should be large.

In my toy example, the country systematically converges to 2% growth, and the R-squared of my little regression is 0.86. PS find much smaller R-squares in their work. The conclusion is that growth rates in the next decade are very unpredictable. So does this mean that convergence and the Solow model are wrong? No. The reason is that once you allow for any kind of meaningful shocks to GDP per capita, the short-run growth rates get very noisy, and you lose track of the convergence. It doesn't mean it isn't there, it just is hard to see.

Let me give you a clearer demonstration of what I mean. I'm going to build an economy that strictly obeys convergence, with the growth rate related to the difference between actual GDP per capita and trend GDP per capita.

More formally, let

$$ y_{t+1} = (1+g)\left[\lambda y^{\ast}_t + (1-\lambda)y_t \right] + \epsilon_{t+1} $$

where ${g}$ is the long-run growth rate of potential GDP, ${y^{\ast}_t}$ is potential GDP in year ${t}$, ${y_t}$ is actual GDP in year ${t}$, and ${\epsilon_{t+1}}$ are random shocks to GDP in year ${t+1}$. This formula mechanically captures convergence to trend GDP per capita, but with the additional wrinkle of shocks occurring in any given period that push you either further away or closer to trend. ${\lambda}$ is the convergence parameter, which I said in some recent posts was about 0.02, meaning that 2% of the gap between actual and trend GDP per capita closes every period.

I simulated this over 100 periods, with ${g=0.02}$, ${\lambda=0.02}$, ${y^{\ast}_0 = 20}$ and ${y_0 = 5}$. The country starts well below potential. I then let there be a shock to ${y}$ every period, drawn from a normal with mean 0, variance 0.25. Here are the results of one run of that simulation.

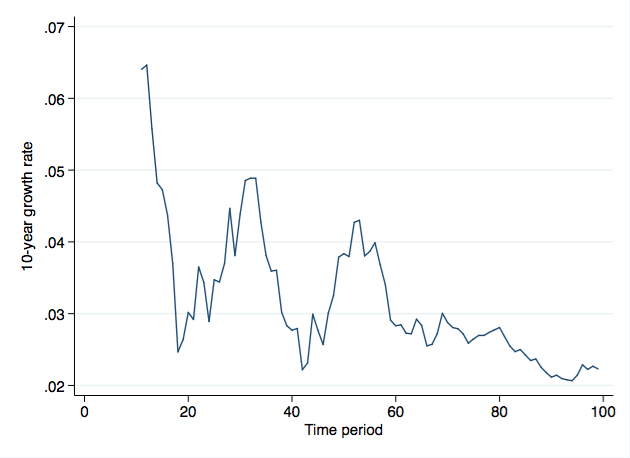

First, look at the 10-year growth rates over time. There is a downward trend if you look at it, but this is masked by a lot of noise in the growth rate. You have what look distinctly like two growth booms, about period 25 and period 50.

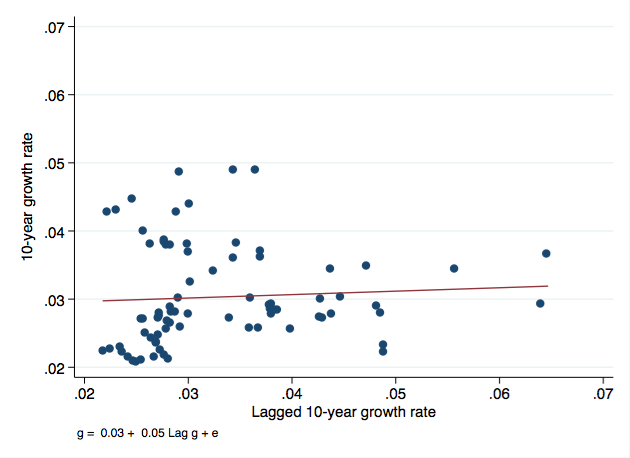

Second, look at the correlation of the average growth rate in one "decade" and the average growth rate in the prior "decade". This is essentially what Pritchett and Summers do. I've also included the fitted regression line, so you can see the relationship. There is none. The coefficient on the prior-decade growth rate is 0.05, so pretty severe mean-reversion. The R-squared is something like 0.16. A high growth rate one decade does not indicate high growth the following decade, and the current decadal growth rate provides very little information on growth over the next decade.

But this model has mechanical convergence built into it, just with some extra noise dropped on top to make things interesting. And with sufficient noise, things are really interesting. If you looked at this plot, you'd start talking about growth accelerations and growth slowdowns. What happened in period 25 to boost growth? Did this economy democratize? Was there an opening to trade? And what about the bust around period 40? For a poor country, that is low growth. Was there a coup? We see plenty of "bursts" of growth and "bursts" of stagnation (or low growth) here. It's a function of the noise I built in, not a failure of convergence.

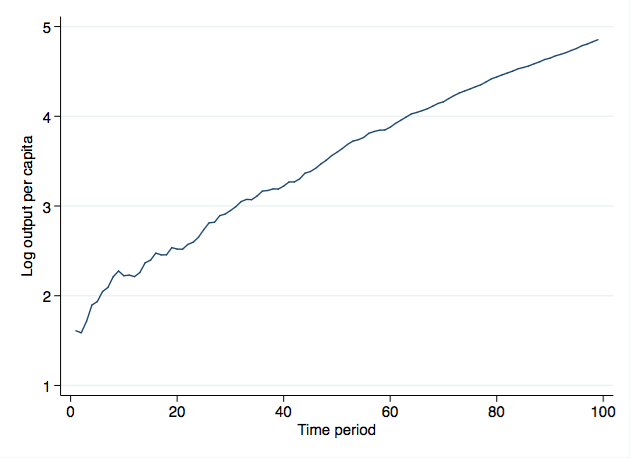

By the way, take a look at the log of output per worker over time. This shows a bumpy but steady upward trend. The volatility of the growth rate doesn't look as dramatic here.

If I turned up the variance of the noise term, I'd be able to get even wilder swings in output, and wilder swings in growth rates. In a couple simulations I played with, you get a negative relationship of current growth rates to past growth rates - but in every case there was convergence going on.

Why are growth rates so un-forecastable, as PS find? Because of convergence, the noise doesn't just cancel out over time. If a country gets a big negative shock today, then the growth rate is going to be low this year. But now the country is particularly far below trend GDP per capita, and so convergence kicks in and makes the growth rate larger than it normally would be. And because convergence works slowly, it will be larger than normal for several periods afterwards. There is a natural tendency for growth rates to be uncorrelated in the presence of shocks, but that is again partly because of convergence, not evidence of its absence. There are lots of reasons that the Solow model could be the wrong way to look at growth. But this isn't one of them.

I think the issue here is that convergence gets "lost" behind all the noise in the data. Over long periods of time, convergence wins out. ["The arc of history is long, but it bends towards Robert Solow"? Too much?] Growth rates start relatively high and end up asymptoting towards the trend growth rate. But for any small window of time - say 10 years - noise in GDP per capita can swamp the convergence effects. In the growth literature we tend to look at differences of 5 or 10 years to "smooth out" fluctuations. That's not sufficient if one wants to think about convergence, which operates over much longer time periods.

PS are absolutely right that we cannot simply extrapolate out China and India's recent growth rates and assume they'll continue indefinitely. We should, as growth economists, account for the gravitational pull that convergence puts on growth rates as time goes forward. But just like gravity, convergence is a relatively weak force on growth rates. It can be overcome in the short-run by any reasonably-sized shock to GDP per capita.

You don't think "Oh my God, gravity is broken!" every time you see an airplane overhead. So don't take abnormal growth rates or uncorrelated growth rates as evidence that convergence isn't occurring.