One of the more intriguing empirical regularities in recent growth research involves population origins. Rather than thinking about rich and poor countries, work by Louis Putterman and David Weil tells us to think about rich and poor population groups (Europeans and Native Americans, for example). Countries are rich if their population is made up of rich population groups, and vice versa. The U.S. is rich because it has lots of European descendants, and relatively few Native American descendants. Mexico, in contrast, is relatively poor because it has a few European descendants but lots of Native American descendants.

The interesting aspect of these findings is that they suggest we are looking at the wrong units of observation, so to speak, in studying economic growth and development. We should be studying the characteristics of population groups, not countries, and looking at the characteristics that make those groups prosperous relative to others.

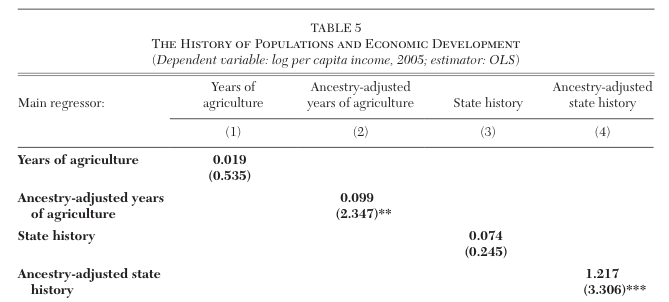

I pulled two sets of results out of the survey by Spolaore and Wacziarg (2013), which is a great introduction to this material if you want more depth. The first are regressions of output per worker in 2005 on either years since agriculture first began or years of "state history" (i.e. how long organized political regimes have existed) for each country. Columns (1) and (3) show that the country-level measures of agriculture or state history are not relevant. But if you weight the years since agriculture began or state history by population composition, you get a different story. As an example, the weighted state history for the U.S. is a weighted average of the state history of England, Germany, Italy, etc.. (quite long) as opposed to the state history of North America (quite short).

The length of time that populations have had settled agriculture and organized states is highly correlated with output per worker today. Countries that have more history with economic organization are richer today.

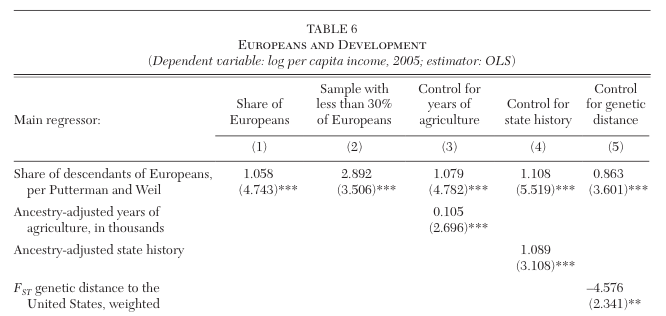

Spolaore and Wacziarg's next table shows that even holding those features constant, the share of Europeans in the population of a country is highly correlated with output per worker today. The upshot is that Europeans and their descendants are rich (as a group), wherever they are in the world, but not so for other population groups. See Easterly and Levine (2012) for more robustness checks on this result.

This idea that some population groups are the source of economic success leads to reactions that run from raised eyebrows to accusations of racism. But let's be very clear that this finding regarding population groups implies nothing about any kind of inherent superiority to Europeans as a group.

We need only a few things to hold for these patterns to arise:

- First, economic organization has to be subject to some kind of cumulative process. Whether you want to call it tacit knowledge, acculturation, or learning-by-doing, successful economic organization must be something that cannot just be snatched out of the ether. Each generation builds upon the prior's organization to become a little more advanced.

- Second, that cumulative knowledge is passed on more easily the more closely related - culturally, linguistically, genetically - are two groups. The English and French can benefit from each others accumulating knowledge more easily than the English and Chinese for example.

- Finally, you need Europe to "get started" earlier than other regions.

With those three elements, you get Europeans with an advantage today in economic organization. They simply got rolling earlier than other areas with figuring things out, and because it is much easier for Europeans to learn from Europeans, they maintain this early advantage over long periods of time.

Further, because economic organization is something accumulated within a cultural group, it moves with them. Hence the United States gains the benefits of the long European history with economic organization, while Mexico does not to the same extent.

Does that mean European-descended places are permanently entrenched as the richest places in the world? It might. The outcome depends on whether other population groups can improve their economic organization faster than Europeans. And this in turn depends on how fast the organization ideas of Europeans spill over or get transmitted to other groups. If other population groups are both learning on their own *and* are acquiring new ideas from Europeans, then they should be catching up. Maybe slowly, but they should catch up.

On the other hand, there could be some kind of increasing returns to scale here, with Europeans getting even better and better at economic organization as they get richer. Combine that with slow spillovers, and the European population lead could not only persist, but widen as time goes on.

If you want to avoid this spiral of divergence, then this literature implies three possible actions. (1) import Europeans, (2) export your people to European places, or (3) assimilate European culture.

Not sure of many places that are actively trying to recruit European settlers (although Paul Romer's whole charter city thing sort of falls in this arena). Lots of developing country citizens do actively try to export themselves to European countries every year.

The last one is probably the most controversial. We can't really tell people in poor countries to "act European"? The whole point is that European culture is this accumulated body of tacit knowledge that is not readily translatable. So how would you actually "assimilate European culture" even if you wanted to? It can obviously happen over time - there are 736 Kentucky Fried Chicken outlets in South Africa - but is this something you can actively manage?

Finally, this means the really interesting question is: how did Europeans get a head start in the first place? The research that Spolaore and Wacziarg review suggests that the advantages go back deep in time. It could be the nature of their agricultural endowments (as in Jared Diamond), or their optimal mix of diversity across groups (Ashraf and Galor), or pure un-adultered luck.

Regardless, studying development in light of this research implies studying population groups or cultures as the units of analysis, rather than confining ourselves to borders that may not have any information content about the economic organization of the populations inside of them.