In my last post I talked about Lant Pritchett's recent article which questioned the focus of the World Bank on only the extreme poor. He wondered whether the Bank was the right partner for developing countries hoping to grow to middle- or high-income living standards. I agreed with Pritchett that poverty alleviation efforts are not capable of generating what we might consider transformative growth, meaning significant convergence towards rich countries.

I got a lot of very thoughtful responses to that post (and one or two unhinged ones). One response came from Emre Ozaltin, who had written an earlier reply to Pritchett. Emre pointed out on Twitter some research showing that health improvements had accounted for 11% of growth in a set of developing countries, suggesting that this means poverty alleviation efforts do lead to growth.

Twitter just isn't sufficient to make a coherent reply, so here we go. Even if health interventions really were responsible for 11% of growth in developing countries, that is not the same thing as saying that health interventions can create fundamental economic development.

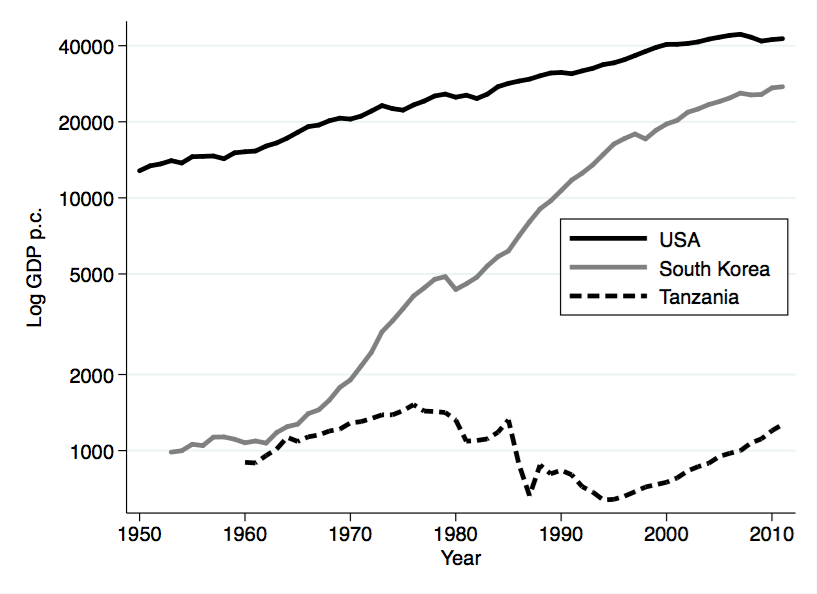

Consider the figure, which shows the time path of GDP per capita in the U.S., South Korea, and Tanzania from 1950 to 2010. In 1960, South Korea and Tanzania are roughly equivalent in living standards. They are both far poorer than the U.S., by a factor of about 10 to 1. In the subsequent decades, though, South Korea and Tanzania have entirely different experiences. South Korea has transformative growth, and the U.S. is ahead of South Korea now by a factor of 1.5 to 1. In contrast, Tanzania doesn't experience much overall growth at all, and the U.S. is ahead by a factor of 42 to 1.

When I talk about and study economic development, I mean the study of what caused South Korea to make that dramatic leap to rich-country status. What will promote that transformation in poor countries? There is no evidence that health or education interventions could be the answer to that question.

When Emre is talking about health generating growth, he is talking about the contribution of health to that mild growth seen in the last twenty years or so in Tanzania. Yes, there was growth. Yes, health interventions were (maybe) responsible for 11% of that growth. But that growth has not been sufficient to do anything to transform Tanzania into the next South Korea.

It doesn't mean that these efforts were a waste, or should be stopped. There is no binary choice between poverty alleviation and promoting transformative growth. I believe firmly that from a humanitarian perspective, we should act to alleviate the conditions of poverty in these countries as much as possible. At the same time, we should also be doing what we can to promote the transformation of these economies, so that they take off in the way South Korea did.

I think Pritchett is worried that the Bank is ignoring transformative growth in favor of focusing only on poverty alleviation. And I agree with him in general that one should not abandon promoting transformative growth. But I don't know that we should worry specifically if the World Bank changes its focus.

From the World Bank perspective, if they do want to focus on poverty alleviation, mazel tov. But do not claim that this is because it is a more robust way to generate fundamental economic development, or because you have somehow "seen the light". You are making a distinct choice to focus on the humanitarian aspect of development, and ignore the promotion of transformative growth.