There’s a nice working paper out by Patrick Wallis, Justin Colson, and David Chilosi called “Puncturing the Malthus Delusion: Structural Change in the British Economy before the Industrial Revolution, 1500-1800”. The big project they undertake here is to mine the probate inventories (along with several other sources) from Britain in this period to build up a picture of the rough allocation of workers across sectors. They do a very nice job of walking through their data sources, and the limitations, in the paper, so let me leave those details aside. In short, they use the reported occupations in wills to back out a picture of the sectoral structure, finding it consistent with other sources based on apprentice records, as well as prior estimates from specific years.

Let’s get to the good stuff. Here is their Figure 7,

The dots refer to prior point estimates from other sources. The lines show their inferred sectoral distribution over time if they force the pattern of structural change to hit the point estimates from other established sources. For those interested, what this establishes is that alternative point estimates (labels with C or M) are basically consistent with the main points estimates (labels with ST or B), based on the authors time pattern of change. That is both a neat way of evaluating your data, with the benefit of not pissing off any potential referee’s.

But that aside, there are a few things about this figure that are very informative:

-

Britain was already incredibly non-agricultural in 1550. Only about 60% of workers in Britain in the late 16th century worked on farms in some capacity. For comparison, in 2010 India had a employment share in agriculture of about 54%, Nigeria 61%, and Malawi 65%. Ethiopia was still at 75% in 2010.

-

Britain experienced a substantial structural shift out of agriculture between 1550 and 1750. From about 60% agricultural to about 40% agricultural. 40% puts Britain in 1750 at about the 2010 level of Thailand (38%), Indonesia (38%), or Ghana (42%). Thus Britain in 1750 is about 260 years ahead of those three countries in terms of the structural transformation out of agriculture.

-

Britain’s structural shift was really slow compared to contemporary developing countries. It took Britain 200 years to drop 20 percentage points from its agricultural labor share. In comparison, Ghana dropped 20 percentage points in the 50 years from 1960 to 2010, Tanzania had a similar drop. South Africa, Peru, Mexico, Egypt, Columbia, and Brazil all saw drops of more than 30 percentage points in those same 50 years.

Meaning What?

The WCC paper is very nice because it builds up a strong base of support for the spotty point estimates that were out there before. Which means we can be a little less hesitant in drawing conclusions, or at least forming hypotheses. Then again, now that Brad DeLong has said some nice things about me, maybe I can just start spouting off and you’ll all believe me anyway. I’ll let you figure out what is what.

Your Bayesian prior on “the probability the Great Divergence had its origins prior to the Industrial Revolution” should get updated to a higher number. Brad’s link from above was about a post I did on the persistence of technological change. That post’s point was that a lot of evidence points to 1500 or earlier as a time frame for when we can start to predict which countries will end up rich, and which poor. The fact that Britain in 1550 is already as un-agricultural as India is in 2010 says that something in 1550 was already “going right” in Britain. Again, we should be digging backwards for explanations. (By the way, digging backward for explanations does not mean digging backwards for policy recommendations.)

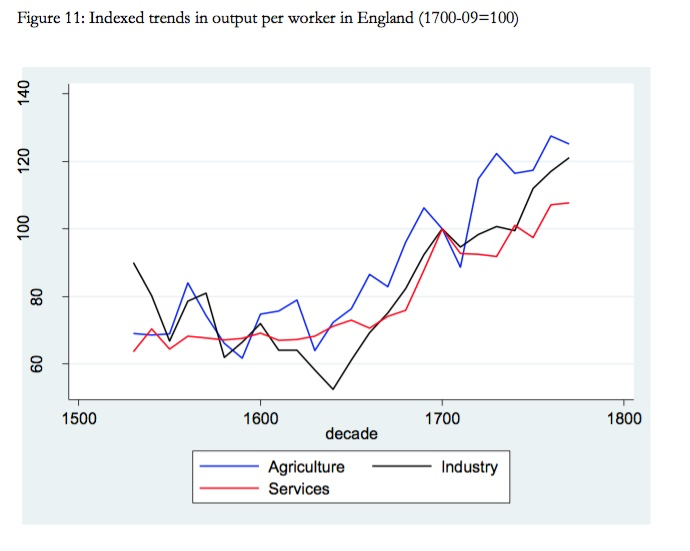

These numbers are bad news if you have “Glorious Revolution” in the “monocausal origins of economic growth” office pool. The data reinforce the argument that the Glorious Revolution was as much a response to economic change, as it was a cause of economic change. WCC provide a rough estimate of output per worker based on their labor allocations and estimates of output from others.

You can see that there is a distinct surge upwards in all three sectors starting early in the 1600’s, well before the Glorious Revolution (1688-89) and the supposed origin of growth-friendly institutions. Britain seemed to be figuring out its economic game well before they imported a Dutch king willing to share power with merchants.

Malthusian Structural Change

While it is in the title, the authors spend very little time talking about how their data “punctures the Malthusian Delusion”. In fact, the terms “Malthus” or “Maltusian” is not used in the main text of the paper a single time. I’m guessing they take as a given that structural change out of agriculture constitutes non-Malthusian economic activity. Hence the puncturing referred to in the title.

But there is nothing about structural change that implies Malthusian forces have been banished, overcome, or left behind. Yes, (too) many papers talking about Malthus give the impression that output in these economies is homogenously made up of subsistence goods like food. But that is just a modeling simplification used to elide the discussion of how labor gets allocated across different activities. An economy operating under Malthusian conditions - a positive relationship of population growth and living standards, and those living standards depending negatively on population size - need not be 100% agricultural.

You could have an economy that had 95% of labor in industry and services, and yet was Malthusian because output was tied to some fixed natural resources (say agricultural land to grow cotton and supplies of coal to heat up the thingies that make the cotton into underpants and tablecloths). You could even get Malthusian forces arising because of urbanization. Your standard urban economics model will imply that stable city sizes occur when the costs of congestion outweight the benefits of agglomeration, meaning that adding more people to a city lowers living standards. Remi Jedwab and I have a working paper using this concept to think about the origin of poor mega-cities.

The point (aside from self-citation) is that Malthusian economies can have rich structural characteristics and dynamics. “Stagnation in living standards over many centuries” does not mean “Everyone living on a farm barely scraping by at the biological minimum requirements for life”.

Britain experiencing a structural change from 1550 to 1750 does not mean it was already experiencing sustained growth. The growth experienced in that period may well have been snuffed out by Malthusian forces of population growth in time. But perhaps that structural change helped bring on the changes in demographic behavior that allowed sustained growth to occur? This structural shift bleeds directly into the Industrial Revolution, which bleeds directly into the demographic shifts involved with sustained growth. Whether this implies a chain of causality is too much to make of this evidence.