There's a paper out in the latest Journal of Economic Perspectives by Decker, Haltiwanger, Jarmin, and Miranda (DHJM) on "The Role of Entrepreneurship in US Job Creation and Economic Dynamism". They document, in more detail than an earlier Brookings report I talked about recently, that the proportion of firms that are "young" has declined over the last 30 years.

DHJM use the number of young firms - those less than 5 years old - as a proxy for entrepreneurship. And therefore the conclusion is that entrepreneurship has declined over the last 30 years. You can see this in their figure 4, below. In 1982, for example, roughly 50 percent of all firms were less than 5 years old, while by 2011 only about 35 percent of firms were under 5 years old. Similarly, the share of total employment in young firms fell from about 18 percent in 1982 to about 13 percent in 2011.

Perhaps most important, the share of job creation from young firms has declined over the same period. In the early 1980's, young firms were responsible for about 40 percent of all new jobs, while by 2011 this was down to about 33 percent. In sum, there are fewer young firms, they employ fewer people, and they create fewer jobs today than they did 30 years ago.

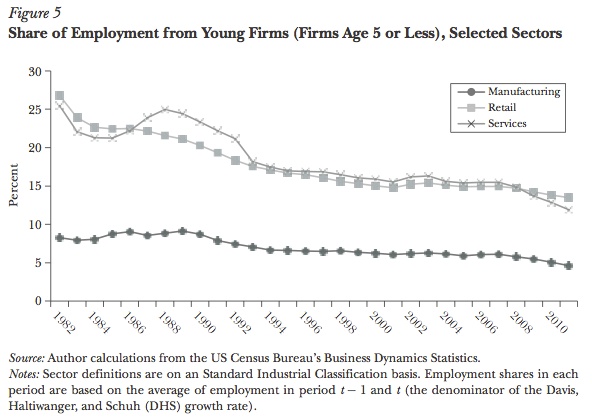

Where is this decline coming from? DHJM show in their figure 5 that for manufacturing, the share of employment in young firms has declined very slightly over the same period, and was never very large to begin with. In contrast, in the service sector the proportion of jobs in young firms was over 25 percent in 1982, and now is around 15 percent. The shift of economic activity from manufacturing to service firms both raised the share of employment in young firms (because of the higher rate in services) and lowered the share of employment in young firms (because of the downward trend within services). On net, the downward trent in services won out, and overall the proportion of jobs in young firms has dropped.

There's nothing to dispute in these numbers, and I don't think DHJM have done anything to misrepresent what is going on. But the big question is: did this decline in the proportion of young firms lower productivity growth? The short answer is, I don't see any evidence that it did. [Update 8/1/14: Just to be clear, DHJM are not claiming that it does lower productivity growth. This is a question I have given their data.]

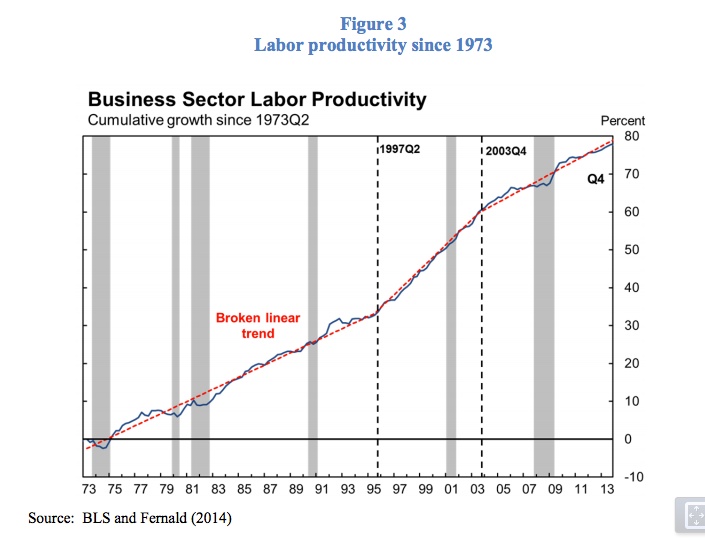

Consider the figure from Fernald's (2014) recent paper on productivity. It shows the trend of labor productivity from the late 70's until today. There is no secular slowdown in productivity growth between 1982 and 2011. Productivity growth from 2003-2011 is just as fast as it was in the pre-1995 period. As Fernald points out, 1995-2003 is an outlier, probably associated with the IT revolution. Therefore, if the decline in the number of young firms is bad for productivity, it hasn't been so bad that it shows up in any aggregate numbers over the last 30 years.

So what does the decline in young firms mean? One plausible explanation is mentioned by DHJM, which is the advance of "big box" or national stores relative to mom-and-pop operations. In 1982, if you saw a niche for a coffee shop in your town, you would open up a coffee shop. Now, a Starbucks was there three years ago. National retailers have gotten very good at identifying lucrative retail locations, and are able to move more quickly than individuals.

Note that this doesn't imply that national retailers are any more productive than mom-and-pop stores (although they do pay higher wages than small retail establishments). If they were, then we should have seen some kind of long-run boost to productivity from 1982-2011. We don't. My guess is that it just means national retailers have a distinct advantage in identifying and opening lucrative retail locations compared to individuals.

Of course, it could be that the loss of productivity from the drop in young firms is offset almost perfectly by the increase in productivity from having national firms more readily identify and take advantage of new retail opportunities. If so, okay. From a productivity standpoint, though, it's a wash, and does not necessarily have any implications for future productivity growth.

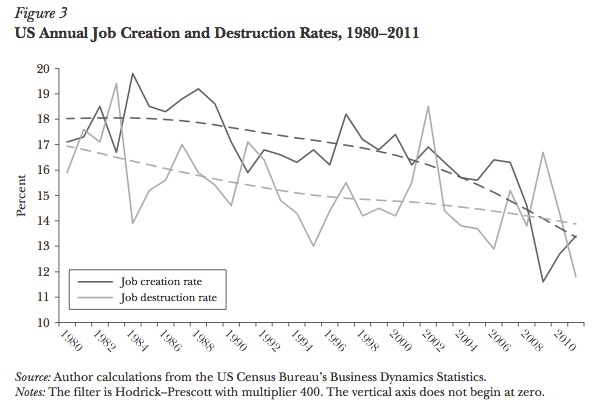

Does it imply anything about employment? Well, as DHJM document in their figure 3, there has been a decline in the job creation and job destruction rates from 1980-2011 (don't get too worked up about the big dip in the trend line for job creation - HP filters are sensitive to the end points you use). Both rates are declining, meaning that there is less worker churn in the economy, which is consistent with less churn in firms, which is what fewer young firms implies. Again, note that the trend of decline in job creation and destruction occurs over the 80's, 90's, and 2000's consistently, which covers periods in which the employment to population ratio rose pretty consistently before leveling off in the last decade.

The fact that the proportion of young firms in the U.S. is declining doesn't seem to be anything to get worked up about, and it doesn't imply that U.S. productivity or employment are doomed to stagnate in the future. If there is some "optimal" amount of young firms to have, we have no idea what it is, and we could as easily be over that amount as under it. For now, I'm mentally filing the decline in young firms alongside the secular shift away from manufacturing and towards services. It's one of those structural changes that occur as economies grow. But evidence from either (a) longer time periods in the U.S., or (b) across countries, could easily change my mind.