I finally got a chance to read through a recent paper by Solomon Hsiang and Amir Jina on "The Causal Effect of Environmental Catastrophe on Long-Run Economic Growth: Evidence From 6,700 Cyclones". The paper essentially does what it says on the tin - regresses the growth rate of GDP on lagged exposure to cyclones for a panel of countries over the period 1950-2008. By cyclone, the authors mean any hurricane, typhoon, cyclone, or tropical storm in this period.

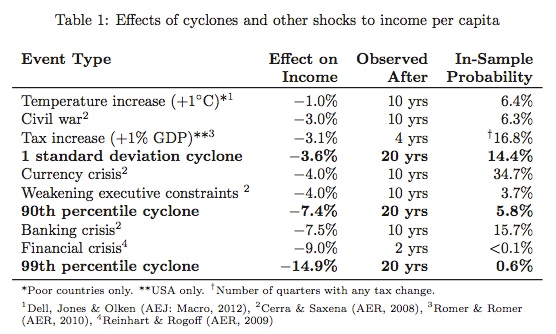

One thing I like about this paper is that they do not bury the lede. Table 1 in the introduction gives you an instant grasp of the magnitude of what they find. They compare the cumulative effect of various disasters on GDP. A storm at the 90th percentile in strength (based on wind speeds and/or energy) reduces GDP by 7.4% after 20 years, similar in size to a banking or financial crisis. This is a big effect. As a point of reference, 20 years after World War II Germany's GDP was already back on it's pre-war trend.

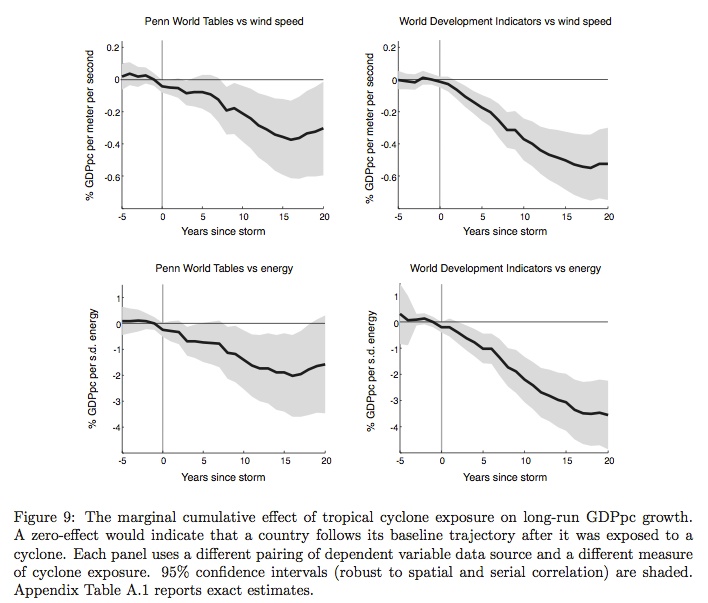

We might think that this is due to particularly slow convergence rates following cyclones. That is, the cyclone is a big shock that pushes the economy below steady state, and then it simply takes a long time for the economy to recover back to that steady state. But Hsiang and Jina's figure 9 shows that this isn't the kind of trajectory we see in places hit by cyclones. The full effect of the cyclone isn't felt until nearly 15 years after. So the cyclones appear to have long-lasting effects pushing economies below their pre-storm trends. This implies some sort of change in behavior - lowering savings/investment rates, increasing depreciation rates, lowering human capital accumulation, limiting technology adoption - something that puts a persistent drag on the level of GDP.

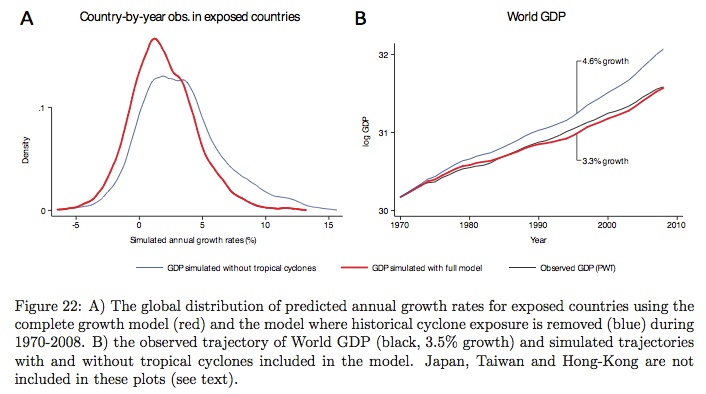

Making things worse is that countries are hit by multiple cyclones over time, and the negative impacts of one cyclone (as in their figure 9) is then accumulated with the negative impact of other cyclones to really push down GDP. They do some counter-factuals with their estimated effects to see what growth would have looked like across countries if there had been no cyclones at all from 1950-2008. Their figure 22 shows the distribution of growth rates in panel A with and without cyclones, and panel B shows the implied growth rate of world GDP with and without cyclones. There's a sizable effect, with world GDP growth being about 1.4% per year higher without these storms.

For particular countries, the effects can be startlingly large. Take the Philippines, which has one of the highest exposures to tropical cyclones of any country in the world. In Hsiang and Jina's counter-factual, GDP per capita would be higher by 2,000%, making the Philippines just about as rich as the U.S. Believable? Maybe not, but it gives you a sense of how much the negative impacts of these cyclones build upon each other through continued exposure. For places like Jamaica, Madagascar, or the Philippines, exposure to cyclones constitutes a persistent negative shock to GDP per capita that is difficult to overcome.

Time for some skepticism. In estimating these effects, Hsiang and Jina use 20-year lags of exposure to cyclones to estimate their effects, and hence are able to create figures like those in their figure 9 above. But their evidence does not rule out long-run convergence back to trend. If the shock of a cyclone is felt over about 15 years, and it then takes 30 years to return to trend, Hsiang and Jina will not be able to identify that. They'd only be capturing the initial negative shock, and not the recovery. This matters because we want to know whether the cyclones have (a) permanently lowered the standard of living or (b) act as temporary (but perhaps long-lived) reductions in standards of living. To put it into regular language, we want to know if the response to a cyclone is "Screw it, I'm not going to bother building a new house at all" or "Crap, it sure is going to take me a long time to rebuild my house".

Hsiang and Jina do look at how exposure effects GDP for different sub-samples based on how repeated their exposure is to cyclones. For countries in the lowest two quintiles of exposure to cyclones, the implied negative effects are very large (I'm having a hard time interpreting the scale on their figure 19, so I'm not sure of the exact magnitude). For the three top quintiles, though, the effects of cyclones are much smaller in estimated size. The estimated effects are negative, and statistically indistinguishable from the effects in their pooled sample. However, the effects are also statistically indistinguishable from zero in most cases - except for the highest exposure countries.

This doesn't quite settle the matter, though. Even though any individual storm may not cause any statistically significant drop in GDP per capita for high-exposure countries, this does not mean that they are unaffected by storm exposure. They may have adopted option (a) above - the "screw it" response - and so have a permanently lower trend for GDP per capita. The Hsiang and Jina paper cannot tell us anything about this, because they are only estimating the short-run effect of exposure to any particular storm, not the long-run adaptation to being exposed (which is differenced out and/or slurped up by the country-level time trend in their regressions).

Regardless, the paper is an interesting read, the latest in an increasing number of studies on economic growth that use detailed-level geographic/climate/weather data. Seeing the effect of the shocks of these cyclones out to 20 years in table 1 is a little startling, and gives you some appreciation for how geographic shocks remain as pertinent as economic ones to growth prospects.