There's a recent working paper by Alexandra de Pleijt and Jacob Weisdorf that looks at skill composition of the English workforce from 1550 through 1850. They do this by looking at the occupational titles recorded in English parish records over that period, and code each observed worker by the skill associated with their occupation. They use the standardized Dictionary of Occupational Titles to infer the skill level for any given occupation. For example, a wright is a high-skilled manual laborer, a tailor is medium-skilled, while a weaver is a low-skilled manual laborer.

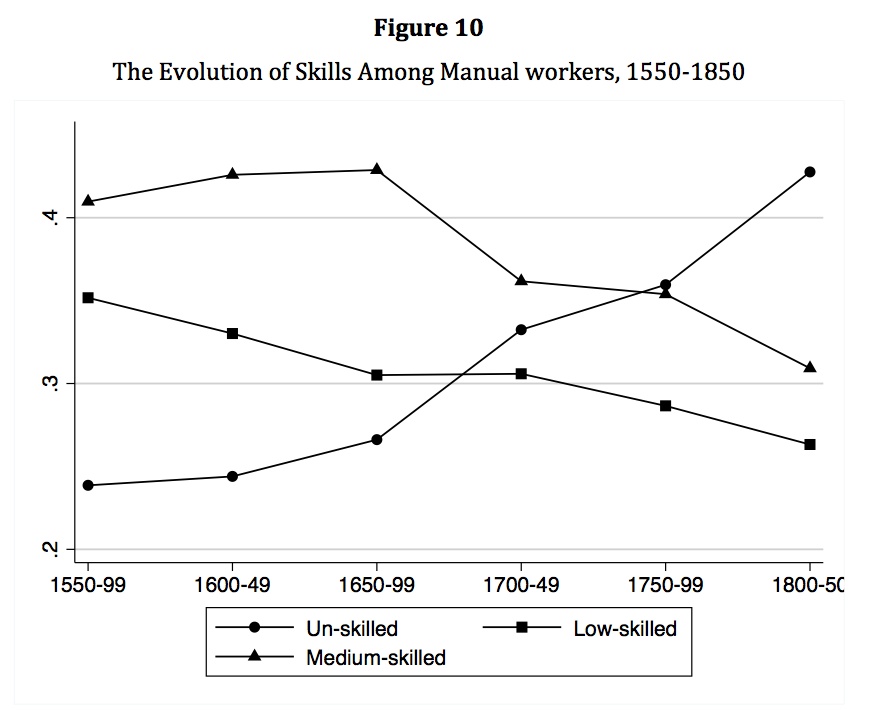

The big upshot to their paper is that there was substantial de-skilling over this period, driven mainly by a shift in the composition of manual laborers. In 1550, only about 25% of all manual laborers are unskilled (think ditch-diggers), while 75% are either low- or medium-skilled (weavers or tailors). However, over time there is a distinct growth in the the unskilled as a fraction of manual laborers, reaching 45% by 1850, while the low- and medium-skilled fall to 55% in the same period. You can see in their figure 10 that this shift really starts to take place by 1650, while before the traditional start of the Industrial Revolution.

Looking at more refined measures, de Pleijt and Weisdorf find that the fraction of workers classified as "high-quality workmen" - carpenters, joiners, wrights, turners - rose only from 3.9% to 4.9% of the workforce between 1550 and 1850. These are precisely the kinds of workers that Joel Mokyr claims are the crux of the Industrial Revolution in England. They built, improved, adapted, and micro-innovated all the classic inventions of the IR. While they were only between 4-5% of the workers, and this proportion didn't expand rapidly, given population growth the absolute numbers of these high-quality workmen went up by a factor of 4 between 1700 and 1850 (from about 200K to 850K).

It's a really interesting paper, and it's neat to see how much information you can keep sucking out of these parish records from England. It leaves me with two big questions/ideas. First, does industrialization depend on a concentrated core of skills, rather than a broad distribution of skills? That is, if Mokyr is right about the source of English industrialization, then it's those extra 650K high-skilled workers that really made all the difference. Industrialization didn't involve spreading skills all around the (rapidly expanding) population, but in getting together a critical mass of skilled workers. Are we paying too much attention to average human capital levels when we talk about development and growth, and not enough to looking at when/how/if countries achieve that critical mass of skilled workers? Is the overall level of education irrelevant to industrialization?

Second, should we care about de-skilling? In a vacuum, telling someone that the share of unskilled workers in the economy rose from 25 to 40% of all workers would send up red flags. That must be a bad thing, right? Is it? As England added population, much of that new population was unskilled, presumably because there was no longer a demand for certain low- and medium- skilled professions that had been replaced by machines. Could this just mean that the economy was getting more efficient at using the human capital at hand? England didn't need to waste all that time and effort skilling-up a big mass of workers. They could be used immediately, without much training.

True, real wages didn't rise between 1550 and 1800 (but from 1800 to 1850 they seem to start taking off, see Clark, 2005). But they also didn't fall. That is, despite the fact that even before the classic IR the population of England was deskilling, there wasn't a demonstrable fall in living standards. So doesn't that imply that England was getting more (output) from less (human capital)? That's a good thing, right? If England had held the level of human capital constant, then this would have raised real wages per worker. Instead, they chose to lower the amount of human capital while leaving real wages per worker the same. Who's to say that this is a worse outcome?

If we were talking about innovations that got more output from less energy, then holding output constant while lowering energy consumption would be what everyone hoped to see. Why should human capital be different?