There is a recent article by Henrik Cronqvist and Stephan Siegel on the origins of savings behavior (published in JPE, but link is for working paper). They use the Swedish Twin Registry, which gives them data on roughly 15,000 twins, and link that to the deep Swedish data on income, savings, employment, and other information. They use this to examine whether savings behavior has a genetic component. Essentially, they are asking whether genetically similar people (twins) have similar savings behaviors. Figuring this out is hard, as twins share not just genes but also share home environments.

To get around this, Cronqvist and Siegel use the differences between identical and fraternal twins to their advantage. Here is the basic idea. If genes matter for savings behavior, then identical twins should have a higher correlation of their savings behavior than fraternal twins because fraternal share (on average) 50% of their DNA while identical twins share 100%. On the other hand, twins of either type will experience similar environmental factors (i.e. parenting). That is, the assumption is that fraternal twins share 100% of the common environment, just like identical twins, and not just 50%.

You have to be careful. Savings behavior can be correlated across twins at 100%, and yet that doesn't mean that genes matter. It may mean that two individuals raised in a similar environment share similar attitudes towards savings. So the absolute level of correlation is not important, but the pattern between identical and fraternal twins is. It is by comparing the correlations within the two groups that allow the authors to draw out the importance of genetics.

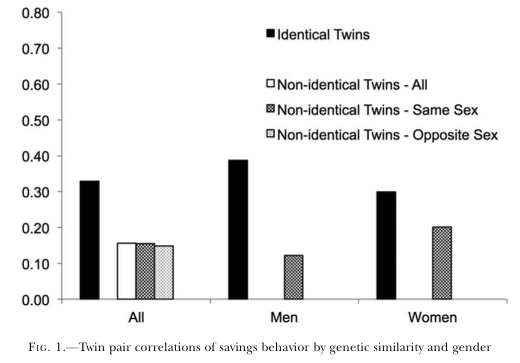

Here's a crude first look at their data:

You can see that identical twins do in fact have higher correlations in their savings rates than fraternal twins. Much of the remainder of the paper is confirming that this figure holds up with various controls included. Perhaps not surprisingly, it does hold up. You can argue with their exact measure of savings (changes in net worth divided by disposable income), but it is a measure used in other papers, and they are not trying to compare across countries so definitional issues in the dataset are less problematic.

The end result is that roughly 1/3 of variation in savings behavior can be accounted for by genetics (a little higher than this for men, and a little less for women). As an example, if you pulled two pairs of identical twins out of the population, you might find that Alice and Agnes saved 15% and 18% of their income, while Bob and Bubba saved 10% and 11%, respectively. About one-third of the difference in average savings (17.5% versus 10.5%) is due to genetic differences between the A girls and the B boys. The A family presumably has alleles that code to more patience on the "savings gene", while the B family has alleles that code to less patience.

Maybe as interesting as the 1/3 number is that the share attributed to common family experience is essentially zero. Their paper supports a "nature" over "nurture" view on savings behavior. For completeness, the remaining 2/3 of variation in savings behavior is purely idiosyncratic. That is, 2/3 of Alice and Agnes's higher saving rate is simply a result of Alice being Alice and Agnes being Agnes.

Do we know what or where "the savings gene" is? No. It is almost certainly not even a single gene, but rather some complex set of genes that combine to determine savings behavior. But what Cronqvist and Siegel establish is that it is reasonable to suspect that this complex set of genes actually exists.

From a growth perspective, research that examines heterogeneity in individual behaviors within economies is often useful in thinking about heterogeneity across countries. This is particularly true when you realize that much of the cross-country variation in economic development is driven by the composition of country's population.

The Cronqvist and Siegel paper cannot tell us whether there are true genetic differences in savings behavior *between* different populations. The genetic variation in savings behavior within Sweden might be similar to genetic variation in savings behavior within Burundi, or Nepal, or Peru. But it opens up the possibility that there could be some genetic variation in savings behavior between countries. If there is a set of genes that code for savings (or patience, or long-run planning, or whatever) then it is certainly theoretically possible that populations vary as well.

Given the relative importance of population composition in accounting for differences in living standards, we cannot dismiss the idea that there is a genetic component involved. Note that this doesn't mean that high-saving or low-saving populations are biologically different, any more than blue eyed populations and brown-eyed populations are biologically different. That is, high-savings populations are not super-patient mutants (who would make the worst X-men ever). They have a gene expression that may lead to higher savings rates.

There are starting to dribble into the research world studies that look at actual genetic differences across populations and the implication of those for economic development. We are no where close to a thorough accounting of the role of genetic variation in explaining development, but it is beginning to look as if we should accept that there is a meaningful role for it.