In a post a few days ago I made a distinction between looking at "measured growth over a few decades" and "the long-run growth rate of GDP". The point was that while we can calculate the former, the latter is something that we have to be more speculative about.

As part of that post, I dropped in a comment about Robert Gordon's work on the long-run growth rate of GDP. I said "He also argues that g will fall due to us running out of useful things to innovate on", where "g" is the growth rate of output per worker. That is a far too glib characterization of Gordon's work. So, first, my apologies to Bob for an unfair comment.

So what *does* Bob say about future growth? He's got several recent working papers out on the subject that you can read to get his full story. See here, here, here, and here. Pulling from the latest paper (the first link), here is his prediction:

Future growth will be 1.3 percent per annum for labor productivity in the total economy, 0.9 percent for output per capita, 0.4 percent for real income per capita of the bottom 99 percent of the income distribution, and 0.2 percent for the real disposable income of that group.

For comparison, note that growth in output per capita from 1891 to 2007 was approximately 2.0 percent per year. So his projection is that growth will be a little under half (0.9 compared to 2.0) of this long-run historical rate.

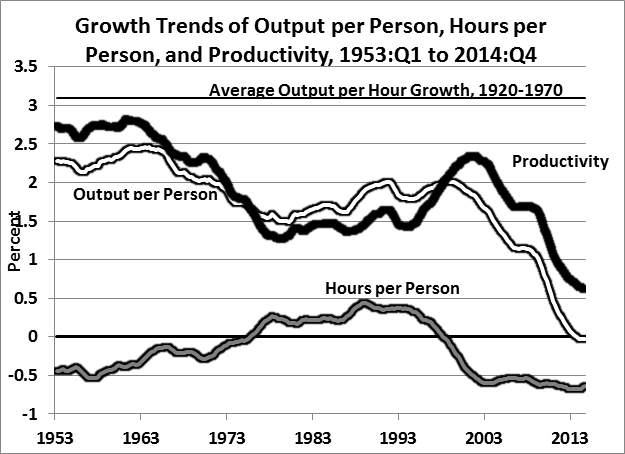

Mechanically, where is this projection coming from? Output per capita is Y/N = Y/H x H/N, where Y is output, N is the number of people, and H is the number of hours worked. Slow growth in output per capita (Y/N) must come from either slow growth in output per hour (Y/H) or slow growth in hours per capita (H/N), or both.

Gordon talks about how demographics, institutional issues in the labor market, and the slowdown in education will limit growth of H/N (and to some extent Y/H). As I mentioned in the prior post, I don't know that these are terribly controversial. He also touches on inequality and globalization as factors affecting not only these growth rates, but the growth rate of income for different parts of the distribution. That's outside of what I want to talk about here, so let's leave it aside.

What does Gordon assume about growth in productivity, meaning growth in Y/H? Gordon does not assume that growth in Y/H will fall in the future (which is what my comment implied). He assumes that growth in Y/H will stay the same as the average rate from 2004-2013, about 1.3% per year.

That is a reasonable thing to do in the absence of any alternative evidence. Given the above figure (which Bob kindly provided), you could even argue that 1.3% is a particularly optimistic choice, as from 2004 to 2013 the growth rate of productivity has been moving down. So Bob is not making a particularly pessimistic claim about future productivity growth, he is guessing it will remain at 1.3%.

Assuming that the growth rate of Y/H will continue at the current average rate could turn out to be wrong. Here is a another figure from his recent paper, on the average growth rate of Y/H in different periods.

If in 1972 you assumed the growth rate of Y/H would be 2.36% per year going forward, you were wrong. If in 1996 you assumed the growth rate of Y/H would be 1.38% per year going forward, you were wrong. If in 2004 you assumed the growth rate of Y/H would be 2.54% per year going forward, you were wrong. So it is quite possible that assuming the growth rate of Y/H will be 1.3% per year going forward is wrong too.

But that doesn't mean Bob Gordon is wrong for choosing to use 1.3% in his projections. I think Bob's criticism of the techno-optimistic literature is accurate. Examples of the cool things that you can do with a 3D printer (or driverless cars, etc..) do not constitute evidence that growth in Y/H *will* rise in the future. In the absence of any compelling evidence that productivity growth is accelerating, using the existing rate is reasonable.

I think the right way to think about this is that Bob has chosen a decent null hypothesis that g = 1.3%. If the techno-optimists are right, then it should show up in the next few years in the data on productivity growth. Give me a couple of years of 3% or 4% productivity growth, and maybe I'll reject the null. But from the perspective of today, I cannot.

Where I disagree with Bob is on the probability that things like 3D printing, big data, robots, and medical innovation could lead to a period of accelerated growth in productivity similar to the 1990s. I think Bob's papers (see section 7 of the most recent one) make it clear that he sees this probability as low (0-5%?). I personally think it is slightly higher (25-30%?), but less than what Brynjolfsson-McAfee would guess (80-90%?).