Paul Romer has a nice post up about how urbanization "passes the Pritchett test" for development. Pritchett's test is that urbanization (in this case) is related both in the cross-section and the time-series to living standards, and positive shocks to urbanization are associated with higher living standards. So Romer argues that we should be studying urbanization as a route towards higher living standards in developing countries. This jives to some degree with his charter city concept, which proposes establishing new cities with functioning institutions in developing areas. There isn't really anything to argue with about the rough correlations in the data. Urbanization is, and has been, associated with higher living standards for a long time.

But there are some subtleties in those relationships that mean simply urging everyone to flood into cities is not necessarily wise. Everything I'm going to talk about now is based on joint work of mine with Remi Jedwab, who studies urbanization in developing countries very deeply.

The first caveat I'll point out is that the absolute pace of urbanization matters a lot. Moving an extra 10,000 people into a city in a year may improve productivity in that city and overall in the country. Moving 1,000,000 people into the same city in a year will probably generate such awful congestion costs that productivity in that city falls and country-level productivity may be lower. Remi and I lay out a simple model of this in a working paper that we have out (and which is being furiously revised right now). We show that if the absolute growth of city population is too large, then city wages will actually get pushed down due to the overwhelming congestion effects, even if there is some exogenous technological progress. That part isn't incredibly shocking. What we then do is show that if population growth is endogenous, and rises as wages get lower, then too-rapid city population growth pushes a city into what we call a poor mega-city equilibrium. The city gets stuck with low wages and high population growth, and cannot overcome the congestion costs of that growth. We explain the arrival of poor mega-cities like Dhaka, Lagos, and Karachi as a kind of perverse result of the mortality transition after World War II, as it raised the absolute growth of cities beyond a critical threshold. Cities like these grow by 400,000 or 500,000 residents per year, while historically cities like New York or London only grew - at their peak - by maybe 200,000 per year. Urbanization that happens too rapidly can have counter-productive results.

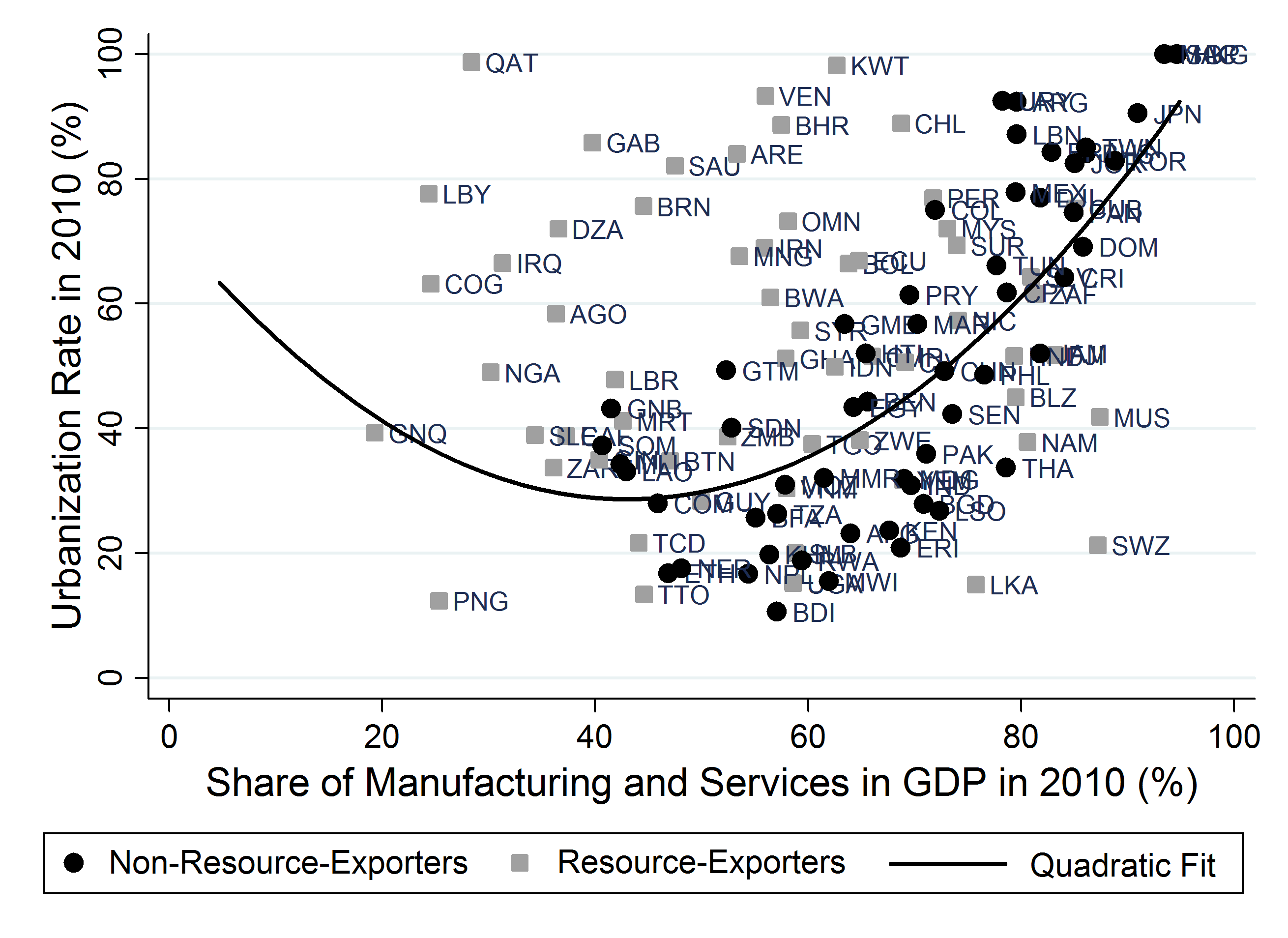

The second caveat is that what drives urbanization matters. Remi and I, along with Doug Gollin, have a paper on urbanization and natural resources. If you look across countries, as Romer does, then there is a clear relationship of GDP per capita and urbanization rates. However, urbanization rates are not necessarily correlated with industry or tradable service production.

The figure above shows the lack of a firm relationship, and this shows up if you use just manufacturing, just manufacturing and finance, or some other reasonable definition of what constitutes tradable goods and services. There are lots of countries in the world that have high urbanization rates, but are not industrialized, and they tend to be resource exporters. And this isn't just places like Dubai. Angola - a major oil exporter - has an urbanization rate equal to China's. We document that natural resource exports are a significant driver of urbanization. We even have a neat little diff-in-diff type specification that looks at discoveries of resources and shows that urbanization rates jump in the decade after the discovery. Perhaps more important, though, we show that cities in places that urbanize because of natural resource booms have very different urban workforces than typical "industrial" urbanizers. Cities in places like Angola have a big percentage of their urban workforce in personal services and small-scale retail trade, and few people in industry or high-value services. This contrasts with China, where their urban workforce has a huge percentage of people in sectors that produce tradable goods or services (i.e. finance). The point is that urbanization is not homogenous. What drives urbanization matters, in that it determines what sectors people in those urban areas end up working in.

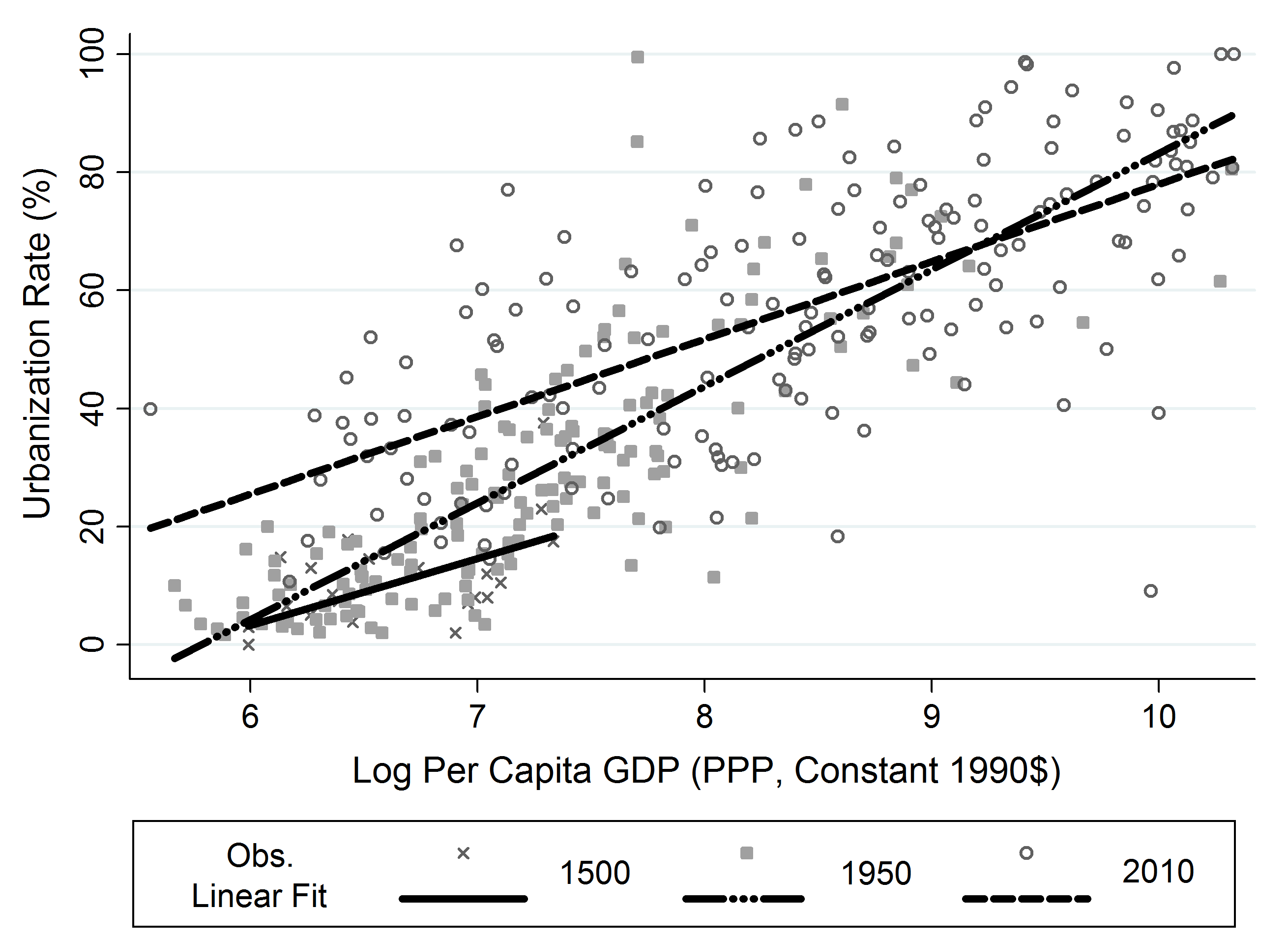

The last caveat kind of takes off from the second. Urbanization has been related to higher living standards over much of history, but that doesn't mean it always will be. Remi and I did a survey paper on the relationship of urbanization and GDP per capita over time. Yes, they are positively related in every year we look at, going back to 1500. But that doesn't mean that urbanization rates have increased primarily because countries have gotten richer.

What we see in the data is that urbanization rates have shifted higher at every level of GDP per capita over time. A country with GDP per capita of $1,000 had an urbanization rate of about 10-15% in 1500, but by 2010 a country with the same GDP per capita would be between 35-50%. Most urbanization over history has occurred not because of countries getting richer, but simply because urbanization has gone up everywhere. One implication is that the positive relationship of urbanization and living standards can only go down in the future. Rich countries are maxed at at urbanization rates of 100%. So if poorer countries continue to urbanize, then the relationship of GDP per capita and urbanization has to fall.

The over-arching point is that the positive relationship between urbanization and living standards we see in existing data is an equilibrium relationship, not necessarily a causal one. There are plausibly negative impacts of too-rapid urbanization on living standards. And Romer is careful in his post not to make any kind of strong causal claim. He thinks we should be studying urbanization more carefully to try and understand what exactly it is that generates the positive relationships. I'd strongly agree with that. I'd like to think that Remi and Doug and I have given some clues towards an answer, perhaps just by pointing out things that are not responsible for the positive relationship.