Every theory of economic growth that I can think of is written to deliver "balanced growth" in the long run. Balanced growth means not only that the growth rate is constant as time goes off to infinity, but also that control variables (the savings rates, the fraction of labor allocated to R&D, the fraction of spending on education) are constant as well as time goes off to infinity.

Growth theories work hard to achieve this balanced growth, often making assumptions about functional forms to ensure that the model delivers balanced growth. Why?

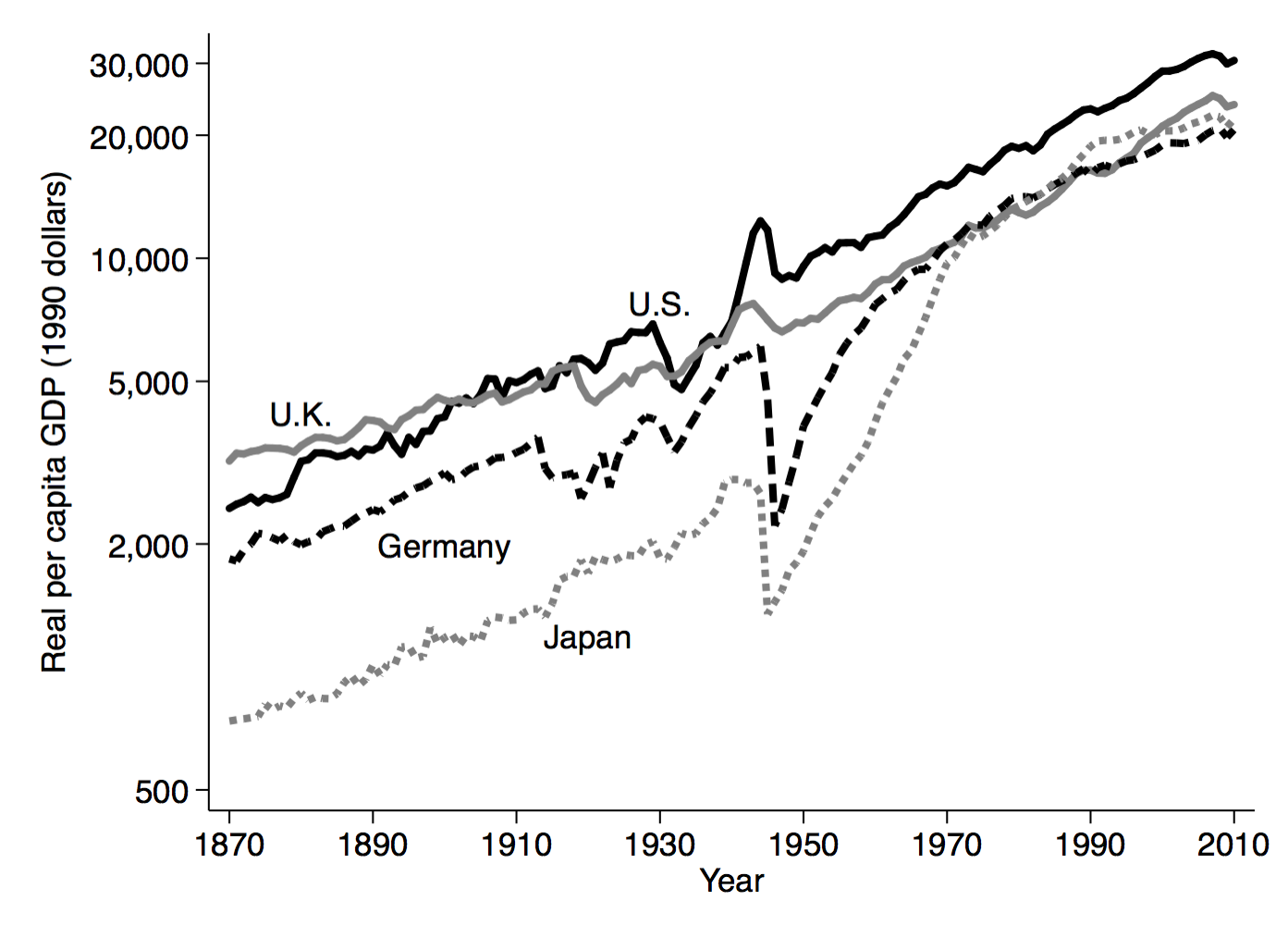

The reasoning is that this is what we see in the data. Output per worker grows at roughly a constant rate in, at least, the major Western economies. If you've read this blog, you've seen a figure like this, which shows the constant growth rate over long periods of time for several economies.

But notice that all this figure indicates is that the growth rate has been constant for a Long Time. But a Long Time is not infinity, and constant growth of GDP per capita does not necessarily imply that we have a situation of balanced growth.

Just because growth is constant, this doesn't mean that the control variables underlying growth are also constant, as is necessary for balanced growth. It is possible that we have achieved constant growth because of a fortuitous coincidence of control variables growing at rates that just offset each other such that output per person grows at a constant rate.

Chad Jones, and in a recent update Jones and Fernald, have explored whether in fact we should think of growth (in the US) as balanced growth or just as constant growth. What Jones originally suggested, and Jones and Fernald reassert, is that the control variables underlying growth in the US are not constant. Hence, the experience of the US up through 2015 may not represent balanced growth. And this in turn implies that we cannot necessarily expect the US to continue to follow the same constant growth rate in the future.

Jones and Fernald break down the roughly 2% growth in output per capita in the U.S. from 1950 to 2007 as follows:

- 0 percentage points due to capital deepening. In short, the capital/output ratio in the US has remained roughly constant.

- 0.4 percentage points due to increasing human capital. This is calculated from the fact that average years or schooling were rising in this period.

- 0.4 percentage points due to scale effects. This captures the fact that increasing population generates more people doing R&D as well as larger markets that increase incentives to do R&D.

- 1.2 percentage points due to increasing R&D intensity, meaning that the share of the labor force engaged in R&D was growing.

Of these, the increase in human capital and the increase in R&D intensity both reflect growth in control variables. In short, neither can grow forever, as they are bounded. Years of schooling is bounded by life-span (and actively removes labor from production) and the share of workers engaged in R&D cannot go above 1. So by necessity, both of those terms cannot continue to grow forever, and hence growth would have to fall below 2% as some point.

We can already see in the data that average years of education is starting to level off at about 14. And so that 0.4 p.p. we got from growing human capital may begin to disappear in the near future.

The percent of workers doing R&D has been generating much of the growth we saw over the last 50-60 years, according to Jones and Fernald. Can this continue? As I said, not forever, as that share is bounded above by 1. But we have to be careful here, as this is not just the share of workers in the US doing R&D, but something like a weighted average of the share of workers doing R&D across all countries. As China and India ramp up their shares, this can continue to pump up R&D intensity for potentially a long time. There is no obvious leveling off of R&D share, as there is with education. So perhaps we can continue on this constant (but not balanced) growth path for decades or a century longer?

Of all the terms above, only the scale effect is not a control variable, and hence is capable of continuing to provide growth forever. This means that the underlying balanced growth rate of the economy may be as low as 0.4% per year. But even that may be an overestimate, as population growth is slowing down over time.

Are we doomed to eventually see the growth rate slow down to 0.4% per year or less? Possibly. But underlying this all is a very distinct assumption about how technology evolves. Jones and Fernald, as well as nearly all growth models, assume that the flow of technology rises as technology accumulates, but at a decreasing rate. This reflects the concept that it is harder to invent new things as the number of technologies increases. By itself this would imply that the growth rate goes to zero, and it is only offset by the growth in the absolute number of R&D workers. If we stop jacking up the share of workers doing R&D, and the population size levels off, then we will no longer be able to offset this tendency for the growth rate of technology to fall towards zero.

But what if the flow of technology doesn't have this tendency to decrease with the level of technology? We make that assumption because it delivers balanced growth in our models, but that doesn't mean it is true. What if AI, or robots, or quantum computing, or BIG DATA, or the singularity, or aliens, or something else means that if we hit a certain level of technology, the flow of new technologies explodes? Then even with a constant number of R&D workers (or perhaps even a declining number) we could see technological growth rise and economic growth with it.

The question of what happens to growth over the next few decades boils down to two sub-questions. (A) Will the intensity of R&D effort level off, or will rich countries as well as India and China continue to push greater proportions of their resources and people into R&D? If so, then growth can be kept close to 2% for a long time. (B) Will there be a fundamental shift in the nature of technological progress?

A little aside from this discussion is that it isn't exactly clear why we work so hard to make sure our growth models produce balanced growth, when we don't necessarily see balanced growth in the data. Maybe its okay if your growth model has a very long-run prediction that growth is zero. We might just be on the transition path towards that zero growth rate, but it takes a very long time to get there. In the meantime, your model could be a good indicator of what is going on.