One of the papers I use to introduce several ideas into my graduate growth and development course is by Diego Comin, Bill Easterly, and Erick Gong, titled “Was the Wealth of Nations Determined in 1000BC?”. If we were being strict about things, the answer is no. But the longer answer is “Well, not really 1000BC. But there is a surprising amount of explanatory power in technology measures from 1500AD”.

What CEG document is that technology levels are incredibly persistent, and that technology levels reaching back centuries retain some predictive power for explaining variation in income per capita in 2002. I’ll hit back below on this idea of predictive power, and how that differs from “causal explanation”. For the moment, focus on that word “persistent” and think about what it means.

We need to think about two kinds of persistence. What I’ll call “time-series persistence” is the idea that for a given country or economy, their technology level in the past is highly predictive of their technology level today. This is different than “cross-sectional persistence”, which is the idea that gaps between countries persist over time. You could have time-series persistence without cross-sectional persistence (e.g. slow convergence to a common technology level) or cross-sectional without time-series (e.g. fixed level differences in technology).

CEG are going to, in the end, provide some evidence of both kinds of persistence. Let’s start with the cross-sectional persistence, which is the main theme of their paper. Here let’s stop to describe exactly how they measure “technology”. CEG use several sources, including the Murdock Ethnographic Atlas, to pull out binary measures of technological use for different ethnic/cultural groups. Did your group use wheeled wagons in 1500? Yes? You get a 1. Did you use paper? No? You get a zero. Did you produce steel? No? You get a zero. Average these 0/1 measures across the different measures of technology, and you get an overall score that lies between 0/1 based on how many of these technologies you had. There is no intensive measure here (i.e. how widespread the use of the technology was within your group), only a coding for whether you used it at all.

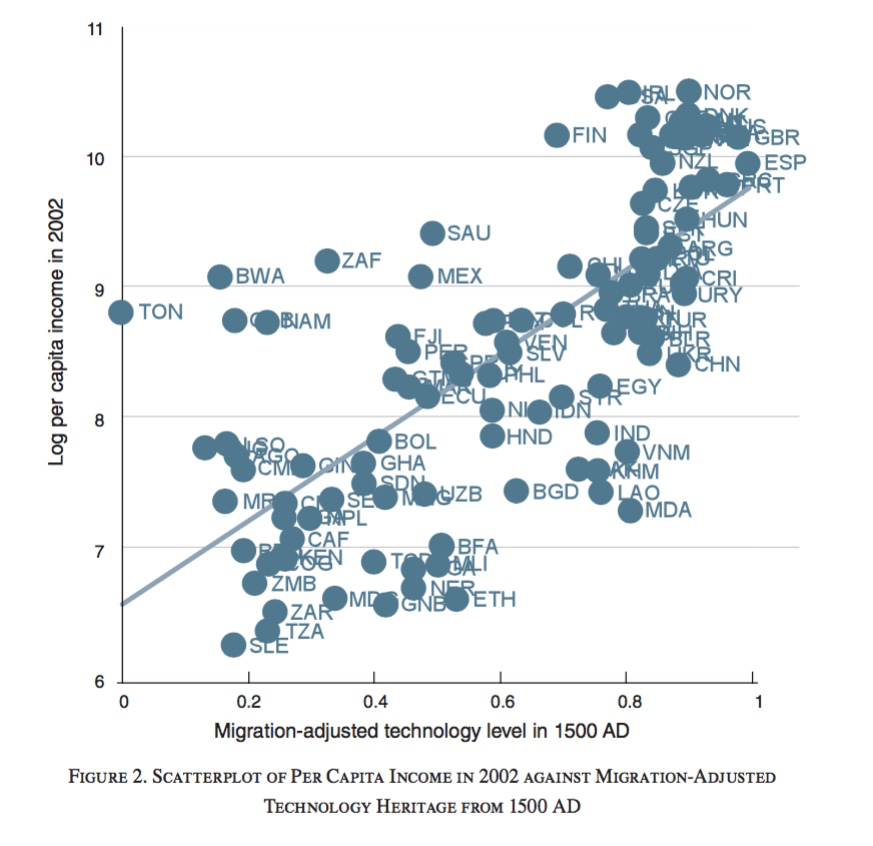

Their Figure 2 gives you essentially the whole thrust of the paper. They use the ethnic group technology measures, assign each country a technology level based on the highest scoring ethnic group in their country, and then adjust the country level scores based on the fact that country populations are different in 2002 from in 1500 (see Putterman and Weil, 2002. Thus they have “migration-adjusted technology in 1500AD” on the x-axis, and log income per capita in 2002 on the y-axis. There is a strong positive relationship. The higher the technology in 1500AD, the higher the expected level of income per capita in 2002.

A few open questions I have is whether this is robust to (a) using the minimum, average, or median ethnic group technology level for a country, rather than the maximum, (b) using all the ethnic group technology data, and run that through the Putterman/Weil matrix to find a country’s technology level.

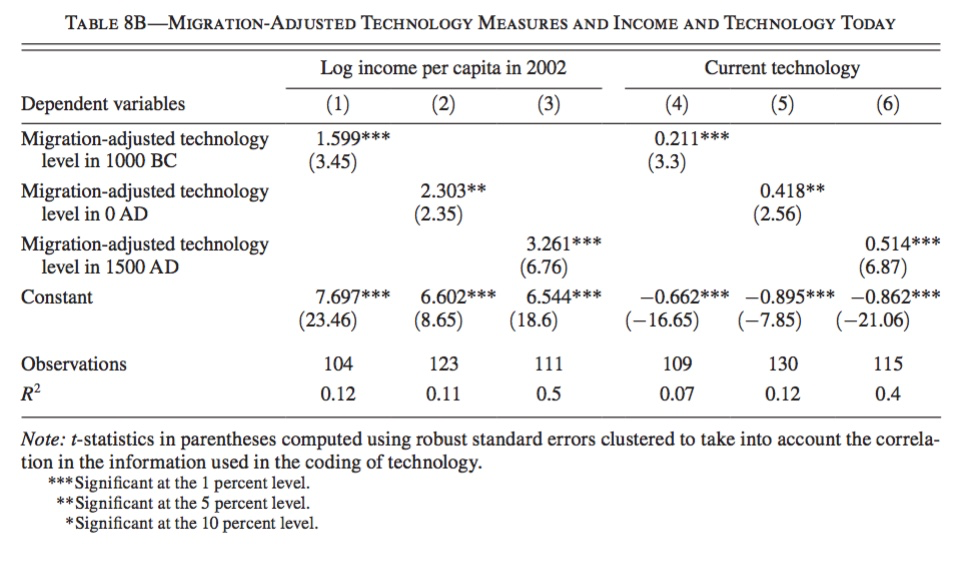

Their empirical results are in the following table. When they regress 2002 current income per capita on technology levels in past years, they find significant effects. This holds for technology in 1000BC, 0AD, and 1500AD. Note that the coefficients rise as the time span becomes shorter. This isn’t surprising, as technology levels are imperfectly persistent.

The size of the effect is surprising. Take the 1500AD result in column (3). The coefficient is 3.261, which means that if the technology index goes from 0 (no technologies) to 1 (all the original technologies), log income per capita goes up by 3.261 log points, or by a factor of $exp(3.261) = 26$ times. Technology doesn’t vary between 0 and 1 in their index, but this gives you a sense of how strong the effect is.

Also notice the R-squared, which is 50% for the 1500AD results. That’s a big number. Half the variation in income per capita in 2002 is associated with variation in technology in 1500AD. It is worth stopping here to say something about what CEG are saying empirically. This is not a “policy experiment” paper, and I don’t think it is appropriate to evaluate it as such. This is a paper about forecasting, basically. What their result says is that if you tell me the level of technology in 1500AD, I can predict with a good amount of accuracy your income per capita in 2002.

That’s different than saying that if one could increase technology in 1500AD by “1 unit”, you could raise income per capita today by a factor of 26. First, as is obvious, there is no way to actually do that. Second, this isn’t the interesting research question here. CEG are trying to establish that old technology levels have predictive power for current income per capita. They are not looking for explanatory power, or forecasting power, and not a strict causal effect.

Should they be looking for a strict causal impact? That’s a fair question, but one without an obvious answer. Ultimately, you might want to argue that we want strict causal explanations for why some countries are rich in 2002. But an explanatory paper like this is valuable to that search. Knowing that anything in 1500AD has strong predictive power for incomes today is informative. It tells us that we have to look back to 1500AD for at least some of those causal forces. Even if it turns out that technology in 1500AD is just a proxy for institutions, or geography, or culture, or whatever, this is a time period we should be looking at.

All this means that CEG have evidence of cross-sectional persistence. Gaps in technology in 1500AD appear to persist for centuries. This doesn’t mean the gaps are perfectly persistent (i.e. will last forever), just that they take a loooooong time to dissipate. Is this surprising? Perhaps not, if you think that there is a lot of time-series persistence in technology.

And CEG provide some evidence of that time-series persistence. Not just in their baseline results from the table I showed, but in a secondary analysis that uses the fact that they have multiple categories of technology. With multiple categories, they have multiple observations on each country in each year. Which means they can look at technology-level regressions while pulling out country-time effects (i.e. England in 1500 and England in 2000 just happened to both be lucky) and technology-country effects (i.e. England is just really good at transport technologies). Here, I need to be clear that their measure of technology in 2000 is not the same as their measure in 1500AD. The measure in 2000 comes from other work by Comin and Bart Hobijn that is richer in measuring how many modern technologies a country has adopted.

Regardless, they show that if a country-technology level is high in 1500AD, then it also tends to be high in 2000. Given the fixed effects included, that is saying that if a technology in England in 1500 was slightly about the average tech level in England in 1500, then it also tends to be above average in 2000. This is a little stronger evidence of time-series persistence, because they are not actually comparing one country to another any more, but one country to itself.

All well and good. But like I said above, time-series persistence doesn’t imply cross-sectional persistence. Why do we see so much cross-sectional persistence. CEG provide a list of theories of time-series persistence, but I don’t know that this is really adapted to the job of explaining the cross-sectional persistence. Many of the theories they document posit no limits on the flow of ideas (spillovers, complementarities, recombinations, etc..) between sectors, people, or technologies. And this makes sense in explaining time-series persistence. But if the ideas can flow, then why not over borders?

For cross-sectional persistence, you need something that actually limits the flow of ideas to different populations/countries. For cross-sectional persistence, it seems unlikely that it really is an inability to invent or copy new technologies; they are out there, easy to see. You need some friction that lies outside of a narrow view of technology. And I think that this pushes you towards theories that are based on culture and institutions (both loosely defined). It seems there must be non-technological factors that prevent adoption of technologies, perhaps because of norms (“we refuse to use things invented by infidels”) or entrenched interests (“we refuse to use things that threaten our monopoly power”).

In that sense, it isn’t the technology in 1500AD per se that matters in the CEG regressions, this is an indicator of some kind of variation in culture or institutions (or something else?) that matters. To return to the earlier discussion, it seems likely that their results won’t ultimately turn out to be causal, but the predictive power is telling us to something about how powerful those cultural/institutional factors are.