A good amount of discussion takes place about how to accelerate growth, with a lot of prominent examples coming from the US presidential primaries. Jeb! promised to get the growth rate of GDP to 4%. Gerald Friedman said that Sanders’ plans would raise growth to 5.3%, and the Romer’s have published a rebuttal saying that is almost impossible to achieve. Narayana Kocherlakota, on the other hand, says that we can adopt policies that can achieve 5-6% growth over the next four years. I know I’ve said before that whatever your favorite policy is, it won’t boost growth rates by maybe more than 1 percentage point, so maybe you could hit 3%.

So what gives? Is it possible, or not, to materially boost growth rates through policy? The answer, which lets you distinguish between the links given above, is that it depends on the kind of policy. To be crude, divide policies into either aggregate supply (AS) policies or aggregate demand (AD) policies.

The big difference between them, at least for understanding their impact on growth rates in the short run, is in whether they involve spending money now. AS policies - reform the tax code, reduce occupational licensing, cut back regulation, etc. - are about changing incentives for people to invest in new capital (human or physical) or to reallocate that capital to higher productivity uses. AD policies - monetary policy, direct transfers - differ in that they directly involve moving money from one person or institution to another. Some policies, infrastructure spending, for example, have elements of both. The infrastructure changes incentives for investments by private business (AS), but also involves a direct transfer of money to pay for it (AD).

To be a little more concrete about my distinction of AD and AS policies, think of the difference between a change to tax law that lowers the tax rate on small businesses (an AS policy) and a $500 tax refund sent to every person in the US (an AD policy). The change in tax rates will presumably induce more small businesses to start or expand (arguing about the size of this effect is something for a different post, roll with it) over time, but this will take time. Nothing material is going to happen to GDP growth this quarter because of that policy change, even though over time it might result in significantly more GDP. In constrast, the tax refund is going to put money in people’s pockets now, and so there will be a more immediate effect on GDP, although it will fade away relatively quickly.

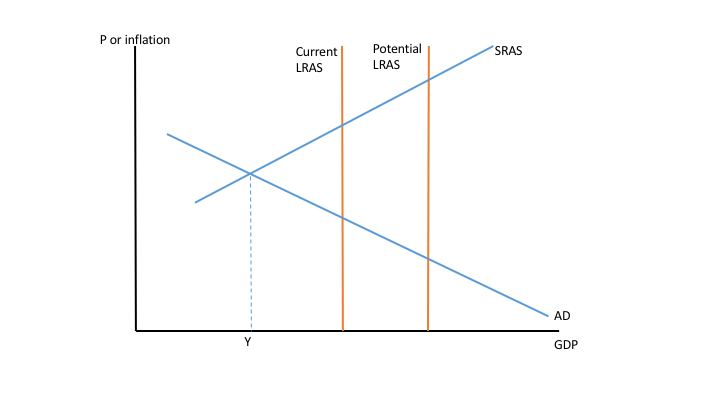

To try and illustrate the difference, let me try some diagrams that should be familiar to anyone who has taken intermediate macro. These are basic AS/AD diagrams, but with an additional feature that comes from growth economics. Rather than one long-run AS curve (LRAS), we have two. The first is the current LRAS, and the second is the potential LRAS curve. In terms of the Solow model, the current LRAS is based on our current capital stock and productivity, while the potential LRAS is the steady state LRAS (To be really true to growth models, we’d say that the potential LRAS curve is slowly moving to the right due to trend growth).

Y is the current level of GDP, determined by the intersection of the AD curve with the short-run AS curve, SRAS. I’ve drawn the diagram such that we are in a situation where GDP is below current potential. I did this to be clear. Being below steady state in a growth model (Current LRAS < Potential LRAS) is a different thing than having “slack” in the economy (Y < Current LRAS).

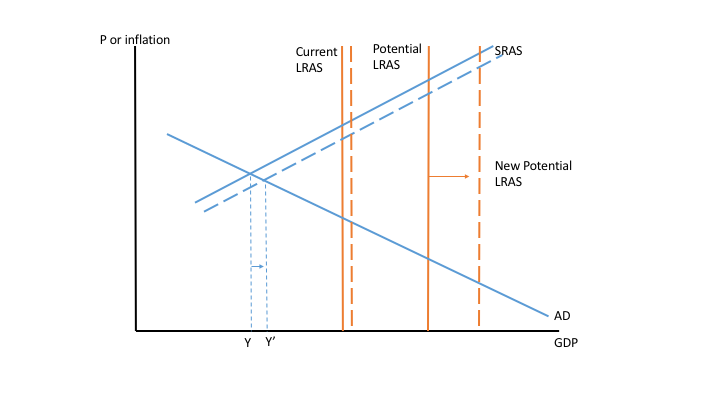

With this I can think through the differences in policies that attempt to accelerate growth, meaning that Y starts to “move to the right” quickly in my diagram. Start with AS policies. These push the potential LRAS curve to the right, but have little immediate effect on the current LRAS or the current SRAS. Over time, the current LRAS will converge to the potential LRAS, but as I’ve talked about before that takes a long time to occur. Note that the fact that the current and potential LRAS are far apart in my diagram to start with is irrelevant. The policies will shift the potential LRAS curve, and we’ll still have to wait for the current LRAS curve to catch up.

Because AS policies don’t shift the current LRAS and SRAS curves by much, the increase in Y is small, and hence there is only a small effect on the growth rate. In the long run, these policies can have a massive effect on living standards, but it can take decades for that to manifest itself.

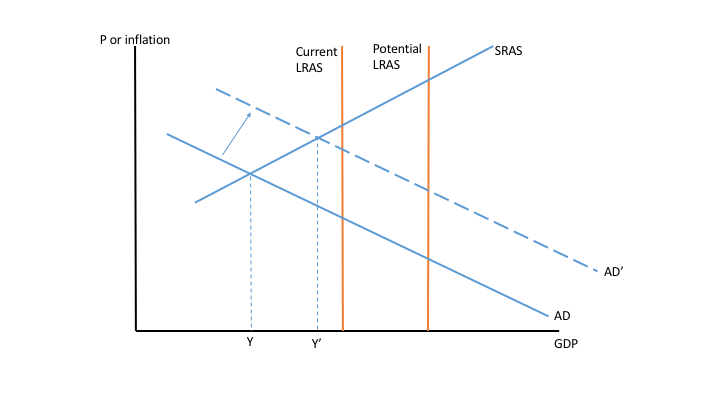

Constrast that with AD policies. These shift the AD curve directly, and close to immediately. I’m perfectly willing to concede that there is some kind of lag in when the AD curve shifts out, but that’s measured in quarters, not decades. Because this AD shift happens immediately, and because the SRAS curve slopes upwards, there is a big effect on GDP from Y to Y’. Note that this depends crucially on the assumption that the SRAS curve is upward sloping. Without that, the AD shift would have no effect.

At the same time, the AD policy has no effect on either potential or current LRAS. And while I’ve drawn the SRAS curve as a line, it probably becomes vertical at some point when GDP is high enough, so you cannot just use AD policies to push up GDP arbitrarily. But if you want to boost growth now, then the AD policies are more effective. A last point is that the size of the effect depends on how far away Y is from the current LRAS curve. Part of the Romer’s critique of Friedman is that he overstates that gap, which thus overstats the power of AD policy.

A large part of the argument about whether you can influence growth in the short run depends on whether we are talking about AD or AS policies. Kocherlakota, for example, explicitly talks about AD policies - monetary policy - as part of his argument for being able to boost growth to 5%. Sanders’ plan is a mix of AS and AD, but I think Friedman got caught up treating all of them as AD plans, which overstated their possible effects in the short run. When I dismissed the ability of various reform plans to boost growth in the short run, it was because they are AS reforms. They will have effects over the long-run, but not in the short run.

Yes, there are probably few policies that are purely AS or AD policies. Monetary policy is probably - unless you don’t buy the classical dichotomy - a purely AD policy. Fiscal policy, on the other hand, seems muddier. It depends on the nature of it. Direct transfers are AD policies (although they might have incentive effects that affect the AS side). Policies that change regulations or the tax code, though, are not really fiscal policy, so much as they are AS policies. Another example might help. Changing education policy to allow teachers to be hired/fired more easily - AS policy. Hiring 1,000 teachers to start teaching this fall - AD policy. A major education reform bill, then, might be both AS and AD at once.

This is one of the attractions of infrastructure spending, by the way. It provides both AS and AD effects. Spend money now to repair bridges, ports, and roads, and immediately boost GDP growth. But at the same time, you are investing in public capital that can incent private business to invest as well, and you are pushing out the potential LRAS curve, which ultimately is the only one that matters.

What all this means is that you cannot just look at the projected growth rate of a plan to assess it. Friedman isn’t wrong because he projects 5% growth, but he’s probably wrong because he is assuming AS policies are going to have big current effects. Kocherlakota isn’t wrong because he projects 5% growth either, but his plan is more plausible because it is based in large part on AD policies. Jeb! wasn’t wrong because he proposed 4% growth, he was wrong because of how he proposed to get there. You can accelerate growth in the short run, but you have to use AD policies to do that. AS policies deliver higher living standards in the long run, but it takes them a long time to ramp up to that higher level.