A whole raft of posts and articles (here, here, here, here) has shown up recently regarding “rent-seeking”. This is kind of a catch-all for increased concentration within industries, more lenient anti-trust enforcement, and the increasing share of corporate profits in output. This is then tied to the slowdown in wages over the last few decades, increasing inequality, and even to slower aggregate growth.

The arguments made by those doing the concentrating and profit-making is that they are promoting efficiency, productivity, and hence growth. Do we know whether concentration or rent-seeking would be good or bad?

I’m going to draw a lot on one of my professors in grad school, Peter Howitt, who along with Philippe Aghion is really one of the godfathers of studying competition and growth. They have a really nice paper with Ufuk Akcigit regarding their “Schumpeterian theory” and how it connects to the data. Schumpeterian theory, for the uninitiated, is growth theory that explicitly deals with firms replacing each other by innovating. This “creative destruction” is what gives the theory its moniker.

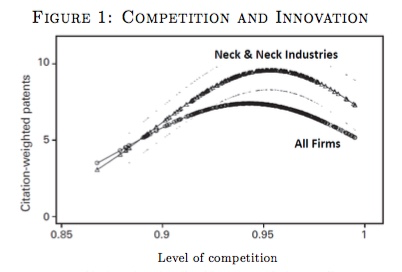

The AAH paper provides a few sets of empirical results culled from various work done by the authors. One of the most interesting is in the figure posted above, using British industry data, which plots patent activity by firms against the level of competition in their industry. Competition is measured by the ratio of marginal costs to price; the inverse of the markup a firm can charge. A higher ratio means MC and P are very close together in the industry, and hence it is very competitive.

What you can see is that patent activity, a proxy for innovation, has this inverted U-shape with respect to competition. That is, increasing competition doesn’t necessary mean more innovation. Why? Because at some point it isn’t worth it to the firms. If you have little market power, what incentive do you have to innovate? In contrast, if you have a lot of market*, then you also are less inclined to innovate, because why bother? You already control market share, and R&D is just a cost.

The “neck-and-neck” industries are just those in which the leading firms are very close in productivity level. They have an additional incentive to innovate (which shows up as their curve being shifted up) because these firms want to try and shed their main competitor.

Regardless, what this figure implies for concentration and growth is that it depends. Concentration and consolidation mean that industries are moving to the left along the x-axis, with less competition. Now, if that industry were already very competitive (close to 1, say), the consolidation may actually increase innovation. But if the industry is already consolidated to some degree, then decreasing competition is going to lower innovation and growth. I have in my head the difference between Marriott consolidating hotel chains around the country in the 70s and 80s, reaping some economies of scale, and investing in improved hotel quality, and Marriott in 2016, buying Starwood. Marriott will probably want to argue that they will still innovate more, but the worry is that they are on the “wrong side of the curve” in AAH’s diagram.

A second result AAH focus on deals with frontier versus backward firms. Here, they again look at British firms, but along the x-axis is the degree of competition measured by the entry of foreign firms into their industry.

For “frontier” firms, meaning those who have productivity levels close to the maximum in the industry, increased competition leads to higher productivity growth. These firms respond to the foreign competition by getting better. But for “non-frontier” firms, the increased entry means they innovate less. Their productivity growth rate actually falls. They don’t try as hard to innovate.

The question with this result is what it implies for concentration. If concentration means less competition (going left on the x-axis) then this implies frontier firms will innovate less, while non-frontier firms will innovate more. But of course concentration implies that firms are buying up one another (or forcing one another out of business). It seems likely that it is the frontier firms pushing the non-frontier firms out of business with concentration. Hence the lower competition would lower the growth rate of productivity in the frontier, and now larger, firms.

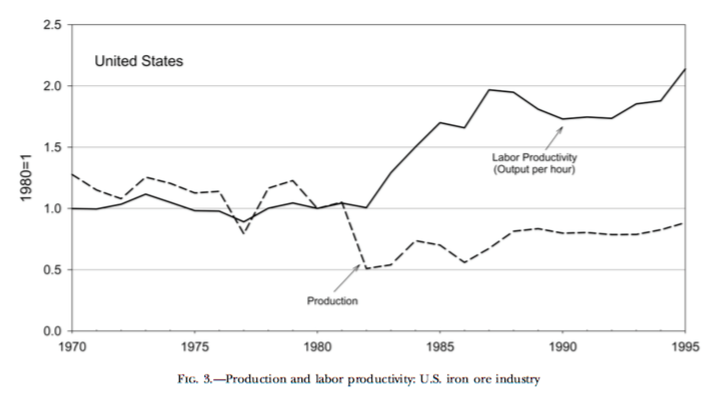

A very nice, specific, example of the effect of competition on productivity is in one of my favorite papers, by James Schmitz. He studies the reaction of the US and Canadian iron ore industries to competition from Brazilian suppliers. They responded by massively upgrading productivity relative to its level in the prior decades. His figure shows the jump in labor productivity in the US industry around the early 1980’s, when Brazil came online.

What’s interesting about this paper is that Schmitz documents how nearly all of the improvement in productivity came through work practices. There was not any massive technical innovation at play here. The competition changed behavior at the producers of iron ore, and essentially got capital utilization rates (i.e. hours of use per day of machines) way up over prior levels. Productivity improvements are not necessarily a function of R&D, these firms could have made those improvements for decades before Brazil entered. But they had a dominant market position, and didn’t need to.

In short, yes, the increasing concentration of industry and rent-seeking, may well be having a demonstrable drag on productivity growth. If this concentration has reduced the need to innovate to stay ahead, because no one can compete with you any more, then this is a negative for growth. Industries, like the iron ore industry prior to the 80’s, that have concentrated market structures with little competition, may not implement even obvious productivity improvements.

If there has been a long-run increase in concentration, decline in entry, and consolidation of market power, then this could be part of the productivity slow-down of the late 20th century/early 21st. Ryan Decker, John Haltiwanger, Javier Miranda, and Ron Jarmin, have been banging on the subject of declining “dynamism” for a while. Ryan’s website is probably the easiest place to find this research all centralized. While I expressed caution that declining new business formation is, by itself, necessarily a sign of slower innovation, the whole body of evidence they have about slower gross flows of workers between firms and firms into/out of existence suggests something is quite different over the last few decades.

Ultimately, and this is my impression, not some kind of established fact, concentration likely lowers innovative activity. Put it this way, the null hypothesis should probably be that concentration lowers innovation. An individual industry needs to provide evidence they are on the “right side of the curve” in the first AAH figure to believe concentration would be good for productivity growth in the long run.