There's a column in the NYT today by Daniel Cohen, titled "When the Growth Model Fails". It is...well, I don't know what it is. A lament? A rant?

Daniel Cohen is a good economist, so it is a shame that the column reads like the work of a politician who occasionally reads the business section of a newspaper. It is a series of disconnected tropes without any meaningful point. It is thick with "truthiness", but nothing in the form of actual facts.

Let's take a look:

And yet, at least in the West, the growth model is now as fleeting as Proust’s Albertine Simonet: Coming and going, with busts following booms and booms following busts, while an ideal world of steady, inclusive, long-lasting growth fades away.

...

But in its desperate search for scapegoats, the West skirts the key question: What would happen if our quest for never-ending economic growth has become a mirage? Would we find a suitable replacement for the system, or sink into despair and violence?

What does it mean that the "growth model" is fleeting? Is Bob Solow fading in and out of existence? I presume that the implication is that economic growth is fleeting, and is coming and going.

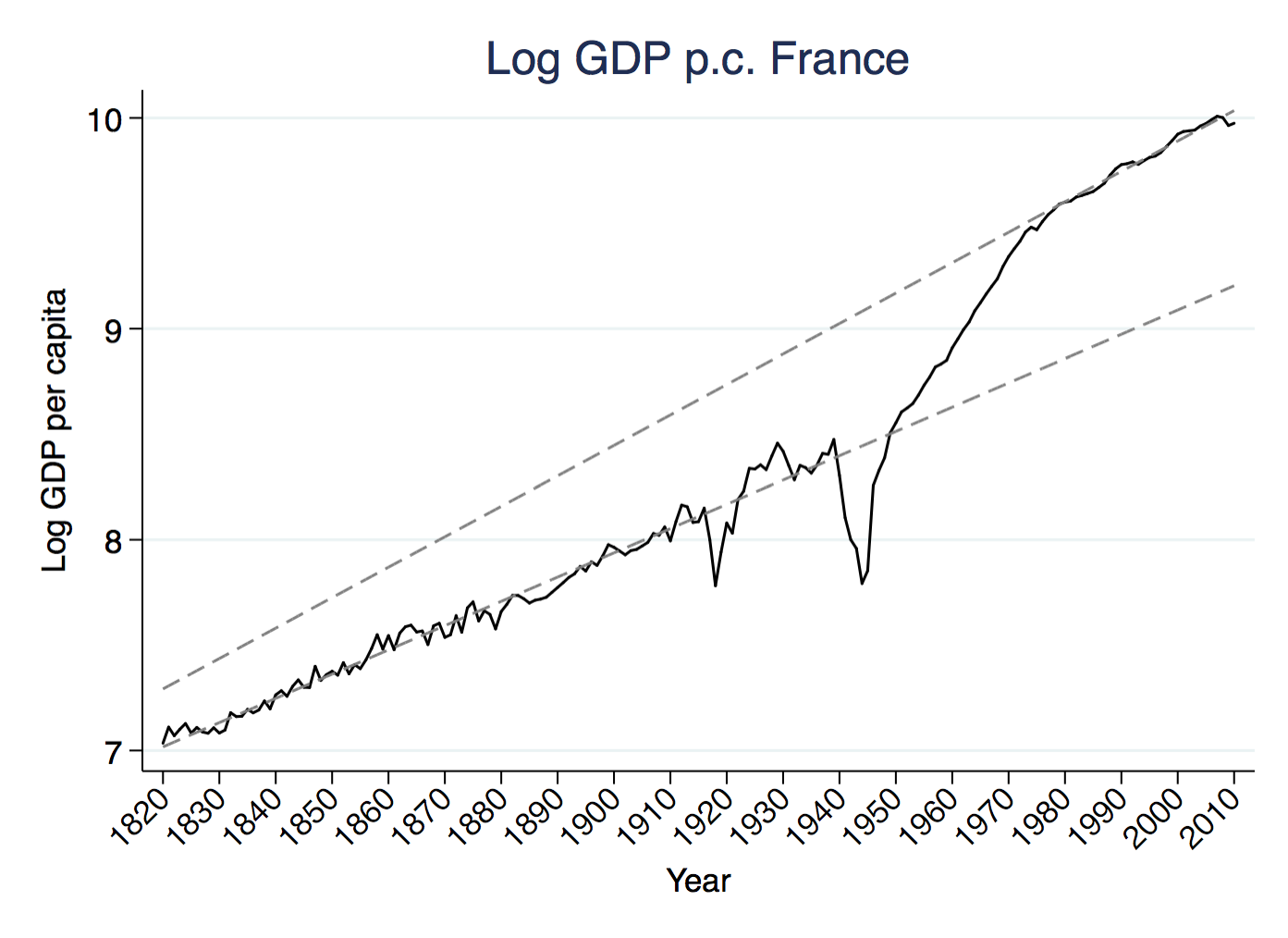

Am I supposed to believe that booms and busts are a new feature of Western economies? That is patently untrue, and Cohen knows this. Business cycles did not start happening in the last decade. A few minutes looking at long-run data (like here) will show you that even in France the frequency and severity of booms and busts were both much, much higher before World War II than after. Took me 10 minutes to download the data for France, plot it, and run some quick regressions. 10 minutes.

"..steady, inclusive, long-lasting growth fades away". You have to unpack this with care. Steady, inclusive, and long-lasting are three separate characteristics, and there is nothing that necessitates that they appear together or in any particular combination when growth occurs. Steady? Again, look at some data. What I see is from 1820 to 1940 steady growth at about 1.2% per year, punctuated by severe recessions and booms. After 1980, I see steady growth at 1.4% per year, higher than the pre-war rate. In between WWII and 1980 I see a country experiencing a level shift to a higher balanced growth path, probably due in part to integration within Europe and technology adoption.

Long-lasting? France has been experiencing steady GDP per capita growth for 190 years. Am I supposed to believe that the downturn you can see at the tail end of the figure in 2007 represents the end of that? That the dip in French GDP per capita in 2007 implies that we either have to "replace the system", whatever that means, or sink into despair and violence? Get some perspective.

I think what Prof. Cohen means is that the era of rapid transitional growth that France experience from 1950 to 1980 is over. Yes, it is. But did you really think that growth of 3.8% was going to last forever, when there is not a single example - ever - of a country growing at that rate in the long run? Again, perspective.

Inclusive? Now here is where we get some traction. Cohen cites that 80 percent of Americans have not seen real wage growth in 30 years. You can quibble with the exact figure, but he's right on. The last three decades have not been good for everyone, particularly in the U.S. We do not have a problem with "the growth model", meaning a problem with economic growth. We have a problem with the "distribution model". So write an op-ed proposing changes to tax rules, or supporting education, or opposing excessive licensing of occupations.

Moving on:

Will economic growth return, and if it doesn’t, what then? Experts are sharply divided.

No, not really. Cohen cites Robert Gordon as a growth pessimist. Gordon is, but he doesn't predict that growth is ending. Gordon thinks that the growth rate of GDP per capita will drop from the historical 1.8-2% per year to about 0.9-1.2% per year. This is primarily due to a slowdown in the accumulation of human capital as the population ages and the rates of college and high school completion level off. So even the pessimists don't believe growth is over, just that it will be slower. Gordon also assumes that total factor productivity growth will be lower than in the past, which is completely unknowable. Gordon gets very "cranky old man" about how useless innovations today are (those kids and their Insta-Snap-gram-Book!).

To decide who is right, one must first recognize that the two camps aren’t focusing on the same things: For the pessimists, it’s the consumer who counts; for the optimists, it’s the machines.

Uh, no. To decide who is right we need data. Like several more years of data to see if in fact growth rates have fallen significantly. I wrote a post about this a while back. We won't be able to to definitively say if growth has fallen below 2% per year until about 2025. Until then, there will be too much noise in growth rates to extract a signal.

What matters is whether they will substitute for human labor or whether they will complement it, allowing us to be even more productive.

Uh, no. Regardless of whether machines/robots/Skynet are a substitute or complement for human labor, we as an aggregate economy will be more productive. Whether particular individuals find themselves displaced and unable to find work depends on their own set of skills. How we treat those people is a distributional question, not a growth question.

The logical conclusion, then, is that both sides in this debate are right: We’re living an industrial revolution without economic growth. Powerful software is doing the work of humans, but the humans thus replaced are unable to find productive jobs.

Uh, no. See above regarding economic growth. It hasn't ended just because we had a recession, and a very bad one at that. On the job replacement thing, see here. We experienced similar kinds of disruptions in the past. Can we handle this with more sympathy towards those temporarily displaced by technology? Yes. Absolutely. Again, that is a distributional problem, not a growth problem.

The point is this: If workers are to be productive again, then we must come up with new motivation schemes. No longer able to promise their employees higher earnings over time, companies will now have to adjust, compensate, and make work more inspiring.

Wait, who said workers were unproductive? Did I miss the part where everyone forgot how to do their job? And this seems close to 180 degrees from how companies would respond to an economy that stopped growing. No growth would mean a lack of new firms and/or new types of jobs, so workers wouldn't have outside options. Firms would have even more power to motivate through fear of losing your job, because there wouldn't be new jobs out there to escape to.

Cohen suggests that firms will have to focus on giving workers autonomy to keep them happy. He cites the Danish situation as one that produces happy workers. They are treated respectfully and given autonomy, and in return they are very productive. They have a significant safety net in place so that people don't have to keep bad jobs just to pay the bills. Denmark self-reports as being very happy.

I am all for "the Danish model". Here's the thing. It's a good idea no matter what happens to economic growth. Why should I wait to see if growth slows down to encourage companies to adopt a more positive work environment? If anything, higher growth rates would make it easier to transition to a system like this because economic growth gives people outside options.

The biggest sin of this op-ed is the lack of perspective. It presumes that we are living through not just a shift in long-run growth rates, but a cataclysmic collapse of them. If you want to make that case, then you have to bring some...what's the word? Evidence.

But bonus points for the Proust quote to give it that affected tinge of world-weary seriousness.