I recently had a student ask me if I was a “Malthusian”. It’s not the first time someone has asked me that, and I’m never quite sure what to make of it. It’s always asked in a way that implies it is a belief system, similar to “Christian”, “Muslim”, or “Packer Fan”.

I’m not sure how to reply. I’m not a Malthusian “believer”, because that isn’t a thing. But I do think that several of Malthus’ assumptions about how economies function, in particular prior to the onset of sustained growth during the 1800’s, are well founded. And those assumptions have implications that help make sense of the world in that period of time. Some of the assumptions Malthus made may still be relevant today, too.

This post is therefore an attempt to lay out what I think Malthusian means, and then I’ll touch on a few alternate uses of the term that are not quite right.

Stagnation in living standards

My concept of a Malthusian economy involves two characteristics. First, living standards are negatively related to the size of population. This would occur if we had some sort of fixed factor of production. Typically, one might say it was agricultural land, but you could just say resources if you like. It isn’t even important that they are truly fixed. So long as the resources are inelastic, whether due to a physical limit or because bringing them into use is prohibitively expensive, you’d satisfy the first characteristic of a Malthusian economy.

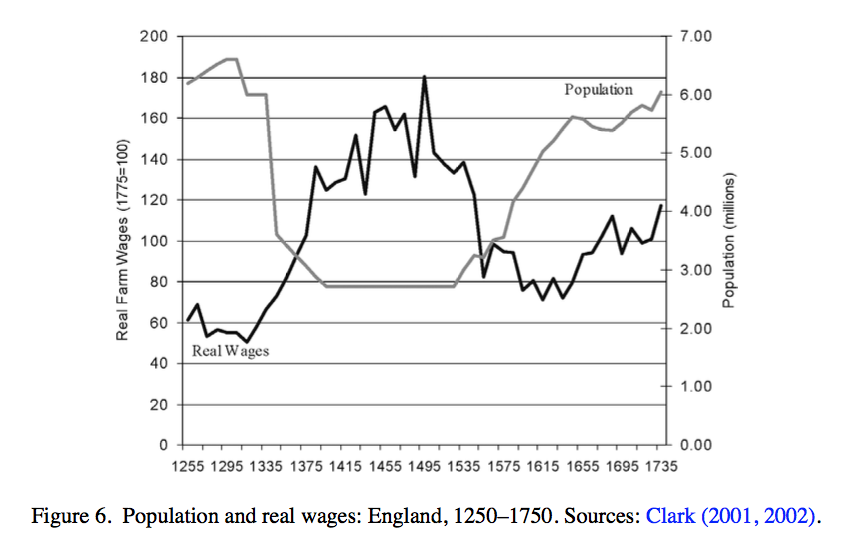

I don’t know that there is much controversy around whether this holds, in particular in the era prior to sustained growth. I cribbed the figure shown here from Oded Galor’s book, which took if from Greg Clark. When population crashes after the Black Death, wages spike. They stay high while population is low, and then fall once population rises again.

The second characteristic is that population growth is positively related to living standards. This may be because kids are a normal good, and so fertility rises when people have higher incomes. Or it may be because health is a normal good, so people take better care of themselves (and their kids) when they have higher income. Higher fertility and/or lower mortality rates would lead to more rapid population growth.

Or maybe people don’t make concious choices like that. Maybe it is purely biological, and women with higher living standards (e.g. healthier diets) will bring more babies to term, and those babies will be more likely to survive to become parents themselves. It isn’t important here whether the fertility and mortality outcomes are subject to rational calculation or not.

Malthus’ original work involved this positive relationship, and he seemed to have in mind a combination of choice and biology. His preventative checks were choices made by people to have fewer children, or marry later, in response to poor living standards (hence living standards and fertility are positively related). His positive checks were lower fertility and higher mortality that would occur somewhat automaticallywhen living standards fell sufficiently far.

Compared to the first characteristic, the evidence for the second is ambiguous. The major issue is that there is little data available on fertility and mortality at the individual level from the period prior to 1800, and so it is difficult to test the relationship of those demographics with living standards. England is one of the places that has some data, and hence the debate on this tends to be over English demographics. Kelly and O Grada (2012) find evidence of preventive checks (i.e. marriage rates), and Cinnirella, Klemp, and Weisdorf (2016) find evidence that births were spaced in response to living standards. But there are a number of studies that conclude the marriage rates were not responsive to living standards. Crafts and Mills (2009), for example, conclude there is no positive check operating, and that preventive checks break down by the 1700’s. If you are looking for reasons to “dis-believe” Malthusian economics, then this is the spot. Perhaps population growth isn’t positively related to living standards after all.

But if this characteristic holds, then you’ve got what I’d call a Malthusian economy. At this point, everything else follows. If there are only a few people, then from the first characteristic we know that living standards are high because the resources per person are high. But high living standards mean high population growth rates, so the number of people expands, and this pushes down resources per person, and hence pushes down living standards.

If there are a lot of people, then the opposite logic holds. Things are crowded, so living standards are low. Low living standards means slow population growth. When things are sufficiently crowded, it will mean negative population growth, and the population falls. Falling population means more resources per person, and so living standards rise.

Everything in the system is pushing back towards some middle ground where the resource per person, and hence the living standard, is at just the right level so that population growth is zero. With no change in population, there is no change in living standards, so there is no change in population growth, so there is again no change in population. The economy becomes stagnant at the living standard which delivers zero population growth. If you’d like a nice treatment of this mathematically, I think Ashraf and Galor (2011) is the cleanest description you’ll get.

Since I’m rambling on about Malthusian economics, let me offer a few observations that are not immediately obvious from what I just described.

The stagnant level of living standards is not necessarily at a biological minimum. Malthus, being something of an eternal pessimist, thought that living standards would be driven down to some bare minimum to survive. This isn’t a necessary conclusion from his two assumptions. Population growth can respond positively to living standards, even if the living standard at which population growth is zero is quite high. It all depends on preferences for kids. All Malthusian economies do not stagnate at the same level of living standards.

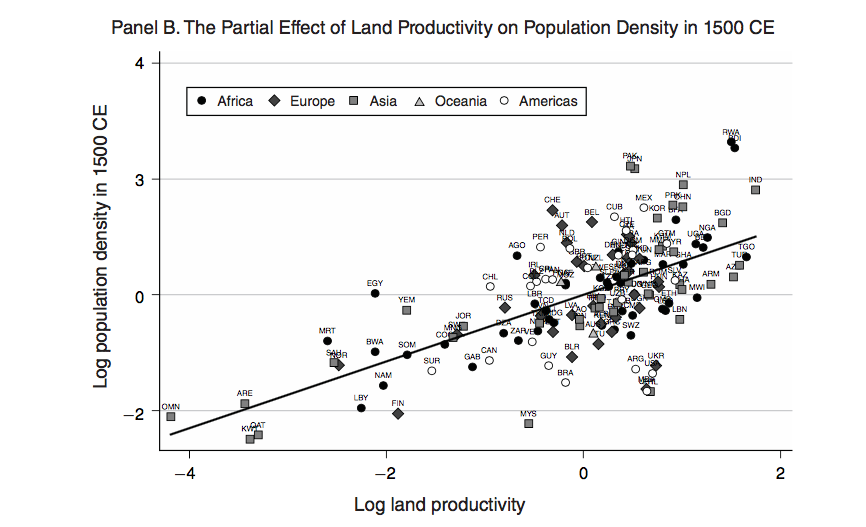

Shocks to technology/productivity will only temporarily raise living standards, but will permanently raise population size. Positive shocks to productivity raise living standards immediately for those alive, but this induces them to have more kids (or induces their kids to not die as quickly, so to speak), leading to population growth, which lowers living standards. Variation in productivity across countries will thus show up in higher population, but not necessarily in higher living standards. This is what Ashraf and Galor (2011) showed in the data.

The first shows that population density is positively related to a measure of land productivity across countries in 1500 CE, consistent with the long-run effect of productivity on population size.

The second shows that living standards (GDP per capita) are not related to the same measure of land productivity across countries in 1500 CE, consistent with no long-run effect of productivity on living standards.

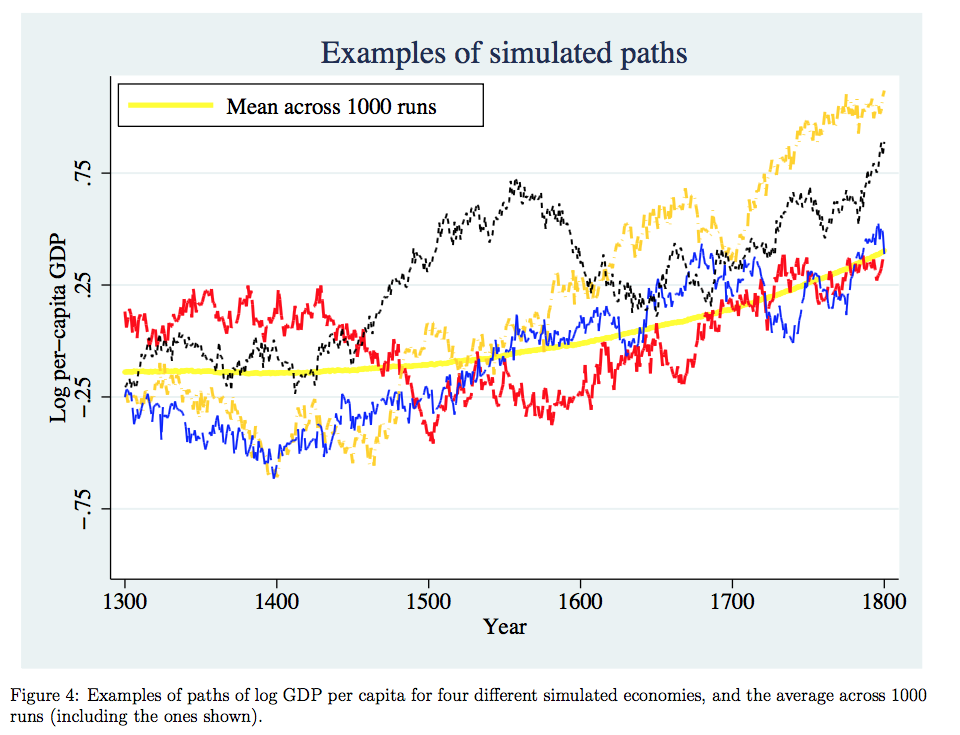

The adjustment back to the stagnant level of living standards can take a long time. This means that a given Malthusian economy may have living standards that wander all over the place in the data. Nippe Lagerlof has a recent paper showing that a Malthusian economy with random shocks to productivity and a realistic age structure will display living standards that do look Malthusian in the sense of being fixed and close to some stagnant level, but display waves of growth and collapse.

Nippe has built a tendency for all economies to move towards sustained growth, but the point is that the four different economies have waves of growth and collapse that last for decades, even though they have the exact same underlying Malthusian structure. The random shocks to living standards persist over time because of the effect on age structure.

So if you ask me if I’m a Malthusian, then I guess the answer is yes, if you mean everything I just said in this section. Now what about other uses of the term Malthusian? Let’s take a look.

Population and factor prices

The term Malthusian has been applied at times to people who assert that changes in population size, acting through factor prices, influence social relationships. Historians like Postan and Le Roy Ladurie advance this kind of thesis, but I think that North and Thomas in The Rise of the Western World may be the purest example of this, and the most known to economists. North and Thomas argue that changes in population, by changing relative wages and the bargaining power of peasants, were instrumental in changing institutions in Western Europe prior to the Industrial Revolution.

People like Robert Brenner and Guy Bois took issue with this explanation (and each other), arguing that Postan and Le Roy Ladurie (and North and Thomas by extension) were ignoring the issue of class in explaining changes in relative wages and the institutions governing labor. Glossing this “Brenner Debate” is well beyond the scope of this post, so suffice it to say that Brenner and Bois argue that changes in population are not sufficient to change institutions. The effect of population changes on labor conditions depended on the actual political power of peasants, which was not necessarily affected by population. See the compilation here for all you’d ever want to know about this debate.

Whatever the details of that argument, and it is a fascinating read, Brenner and Bois use the term Malthusian to describe their opponents and their theories. And to me, this is an incorrect use of Malthusian. The concept that population size influences wages is not Malthusian, it is economics-ian. There is nothing Malthusian about Postan, Le Roy Ladurie, and North and Thomas, at least when it comes to their explanation of institutional change. This doesn’t make Brenner and Bois wrong. It makes them semantically confusing.

Limits to Growth

The third way I think Malthusian gets used is in terms of limits to growth, environmental collapse, and the like. Here, the authors or speakers believe firmly that there is a fixed supply of resources available, and hence living standards must be negatively related to population size.

You can class the limits to growth people into two groups. The first takes population growth as given, and doesn’t think much about whether it responds to living standards. The fact that population growth is positive - at the global level - is sufficient to create declining living standards, and thus we need to either conserve resources or exert some kind of birth control policy. The second group has internalized the post-demographic transition negative relationship of living standards and population growth. Once the planet gets so crowded that living standards fall, this will raise the population growth rate, and we’ll be in a death spiral towards misery.

The view, of either group, is often called Malthusian because of the negative effect of population on living standards. And that, it seems, is only about half right. There is no stagnation in the sense that I described above, as in either case population growth continues (slowly or in an accelerating manner) until the living standard is zero. Which I guess would be stagnant, if it stayed at zero.

Regardless, I don’t consider myself a Malthusian in this sense of the word, and that is because the finite limit of resources gets progressively looser over time. This post is already stretched out too long, so I don’t want to get into a lot of detail here. But there are two reasons for this. First, because technological change will make some resource constraints less binding or eliminate the need for certain resources. Second, because the income elasticity of demand for resource-intense goods is low, our use of those resources will not grow as fast as limits to growth types would suggest.

Note that my original description of Malthusian economies ignores this second effect, coming through income elasticities. Ashraf and Galor’s model, for example, would suggest that no matter how high productivity got, we are always producing goods using the same resource-intense production function. That may be fine if you are just describing the stagnant economies prior to sustained growth - or maybe it isn’t fine, if you read Lemin Wu’s paper - but breaks down if you allow for any appreciable non-resource based sector (e.g. services of any kind).