Comparing living standards in the deep past

Did life suck?

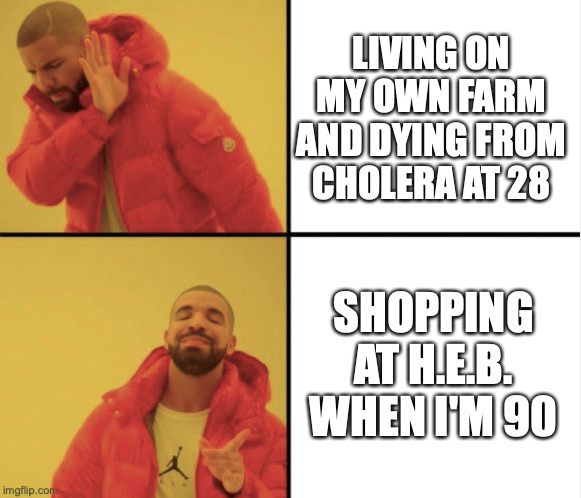

What we’re after here is a comparison of living standards not just with last year or a decade ago, but a century ago or more. Set aside the precise measurement of GDP per capita for the moment. Were people better off before the industrial revolution and the origin of sustained growth in GDP per capita? Or were they better off in a pre-industrial economy based primarily on agriculture?

Jason Hickel wrote an op-ed arguing that rosy outlooks on the decline in poverty (promoted by Bill Gates, in this case) during the 20th century (meaning post-industrial) were wrong. In fact, Hickel argued poverty increased over time due to industrialization.

In other words, Roser’s graph illustrates a story of coerced proletarianisation. It is not at all clear that this represents an improvement in people’s lives, as in most cases we know that the new income people earned from wages didn’t come anywhere close to compensating for their loss of land and resources, which were of course gobbled up by colonisers. Gates’s favourite infographic takes the violence of colonisation and repackages it as a happy story of progress.

That op-ed sparked some responses. Marian Tupy published a reply in three parts, asserting that the “romantic ideal of plentiful past if pure fantasy”. The first of those responses is here, which includes this:

I wish to focus instead on Hickel’s assertion that people in the past didn’t need money “in order to live well”. In fact, lives of ordinary Western Europeans prior to the Industrial Revolution were dismal and fully in accord with Roser’s definition of “absolute poverty.” Put differently, poverty was widespread and it was precisely the onset of industrialisation and global trade that Hickel bemoans, which led to poverty alleviation first in the West and then in the Rest.

The two follow-ups look specifically at urban poverty in the past, and then rural poverty. That last link cites work by historian Carlo Cipolla, who said the following:

“We do know,” Cipolla writes, “that the mass [of the population] lived in a state of undernourishment. This gave rise, among other things, to serious forms of avitaminosis. Widespread filth was also the cause of troublesome and painful skin diseases. To this must be added in certain areas the endemic presence of malaria, or the deleterious effects of a restricted matrimonial selection, which gave rise to cretinism.”

Conditions in 1915

A different way of assessing whether we are better off (whatever that might mean to you) in 2020 than in 1920 is by asking what it would take to get you to go back in time. Would you go back 100 years if you could be a millionaire in 1920? Would you do it if you could be a billionaire in 1920? Don Boudreax took on that question, and makes the argument that you would not do it even if you were as rich as John D. Rockefeller, the richest person around a century ago.

His argument is based on comparing a number of practical differences in technology between then and now. The Bureau of Labor Statistics has a much more thorough description of conditions in 1915 available, and you can make you own assessment.

One thing to note here is that this question is based on real technologies, and not on the level of real GDP per capita. This points out that the number associated with real GDP per capita doesn’t mean anything by itself. Changes in real GDP per capita - economic growth - are a useful summary statistic for how the availability of goods and services changed over time. But real GDP per capita sort of melts all those technological changes together into a single number. Looking at the practical differences from 1915 to today gives you a sense of what exactly differs, and why those changes in real GDP per capita indicate a higher living standard.

The myth of the comfortable peasant

Patrick Greeley has an essay on this whole topic, and I encourage you to read it. He goes through a set of basic claims about how things were better in the “past”.

- Did peasants work less than you? No. Although they may have worked fewer hours for formal pay, they worked more hours overall doing things like chopping wood so they would not, you know, die.

- Did peasants pay less in taxes? Very much no. In addition to monetary taxes, peasants often had to hand over 1/3 or 1/2 of any farm output to lords, and typically owed the owner of their land a fixed amount of labor each year on the owner’s property, up to like 2 months.

- Did peasants eat better than you? Again, very much no. They didn’t eat Cheetos, sure. But they also rarely had fresh fruits or vegetables, ironically, because those things are only in season for limited times in their year. They were also regularly exposed to famine if local crops failed.

- Were peasants healthier than you? No, and don’t get hung up on the “fresh air and exercise” thing. They were outdoors and doing hard manual labor, not on nature walks. They did not ingest any microplastics, but they were ingesting fine particulate matter by the lungful from the fires they used to heat up their unventilated homes. Child mortality rates were such that 40% of all kids died before they turned 15. Try to conceive of almost half of your middle school dropping dead, most likely for reasons (e.g. infection) that you could cure today with a $5 treatment of anti-biotics.