Real GDP per capita and living standards

- Real GDP, not well-being

- Health and life expectancy

- Social changes

- Environmental quality

- Becoming better off?

Real GDP, not well-being

The focus of a course on economic growth is going to be on real GDP. But it is important to be conscious of what real GDP is measuring, and what it is not measuring. Real GDP captures the value of goods and services produced by the economy in a period of time (e.g. a year). Those goods and services are certainly relevant to our well-being, but are not the only thing that matters. Well-being (or utility or welfare) depends on conditions in our lives that extend beyond current economic production.

We should be careful, therefore, in assuming that higher real GDP, or more rapid growth in real GDP, necessarily means we are “better off”. But at the same time, we should not necessarily dismiss real GDP as irrelevant. Many of the things we might consider more concrete measures of well-being - life expectancy, general health, environmental quality - are affected by our ability to produce goods and services. In many cases, an increase in real GDP is associated with more of those things that affect our well-being. In other cases, increases in real GDP are associated with worse outcomes.

Health and life expectancy

Over time and across countries, countries that have a higher GDP per capita also tend to have longer life expectancy. The relationship here probably works in both directions: richer countries can provide better health care, but healthier countries are also able to produce more goods and services. But higher GDP per capita is associated with living longer.

At a finer level, higher GDP per capita is also associated with lower mortality rates, particularly among children. Technological innovations (antibiotics, hand-washing, better neo-natal care) contribute not only to higher GDP per capita, but lower child mortality. This seems to hold both over time and across countries.

That said, not all health indicators necessarily improve as countries get richer. Most countries tend to get fatter as GDP per capita goes up. While overall mortality rates fall (and so life expectancy goes up) their populations tend to suffer more from things like heart disease and diabetes. In one sense, these are “rich country” diseases.

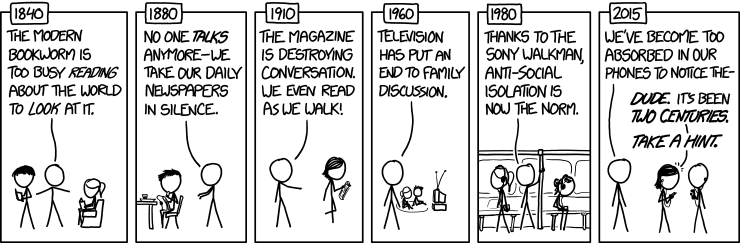

Social changes

As countries get richer, there also tend to be significant social changes. One very apparent change is that in richer countries women tend to have far fewer children. This is probably due, in part, to the lower levels of child mortality already discussed. But in addition, as countries get richer they appear to favor investing more in each child, and less on investing in having more children.

In the same way that fertility falls as GDP per capita rises, the location of most economic activity and residence changes. Richer countries tend to be more urban countries. A significant portion of this is due to the technological innovations that allow fewer and fewer people to supply the food needs of the overall population. So the proportion of people who need to live on farms declines and the proportion that lives in cities increases. There is also evidence that cities accelerate technological innovation, so that urbanization and growth in GDP per capita reinforce one another.

Environmental quality

The relationship of growth in GDP per capita to environmental quality is not universally negative. For many countries increases in GDP per capita are associated with higher environmental quality, as people demand not just “more stuff” but stuff that has less of an environmental impact. If you’re hungry, you may not care much if large amounts of chemicals are emitted by a fertilizer plant. But once you are rich enough to not be worried about imminent hunger, you may start to demand that the food is grown in more environmentally friendly ways.

One example of these kinds of changes can be seen looking at outdoor air particulate matter. As very poor countries get richer, they see higher air pollution levels (look at Burundi versus India, for example). But as countries continue to get richer, air pollution goes down as countries demand cleaner skies (look at India versus the United States).

At the same time, CO2 emissions do appear to rise with GDP per capita, in line with higher energy use in richer countries. There isn’t any evidence in this figure that there is a similar “hump-shape” to energy use, and hence one of the worries surrounding higher GDP per capita around the world is that it will lead to even more CO2 emissions.

Becoming better off?

There is no definitive way to evaluate well-being, and so no definitive way to know if economic growth has made people better off over time. However, I would argue that on balance economic growth has been associated with higher well-being. A few of the key metrics I would consider include the following.

First, lower hunger. At a most basic level, economic growth relieves perhaps the most severe limit on well-being people endure, hunger. Countries that have higher GDP per capita have fewer people exposed to severe hunger.

Second, thanks to increased productivity we have been able to experience both higher GDP per capita (more goods and services) while also exerting less effort to get those goods and services. As countries have gotten richer, they’ve translated that into a decline in the number of hours that people work per year.

Finally, self-reported measures of happiness and life satisfaction are all positively related to the level of real GDP per capita. That doesn’t mean that all that matters to life is consumption of goods and services, but the entire package of outcomes associated with higher GDP per capita (higher life expectancy, lower child mortality, less hunger, lower work hours, etc.) are associated with a more satisfied population.

While the focus solely on growth in GDP per capita does limit the study of economic growth, it doesn’t ignore other aspects of well-being. And the process of economic growth may in fact be part of what drives those other aspects.