Taxes, government, and Growth

Basic relationships

It is normal to think about how government policy - taxation, spending, and regulation - influence the economy. In this section we’ll focus on how these policies influence economic growth. To start, let’s just look at whether there are any meaningful relationships between things like taxes or spending and economic growth.

One might suspect that if a larger share of GDP is accounted for by government decision-making (as opposed to individual or firm decision making), this could influence growth, as the government is likely to be spending on different types of goods and services than private entities. So does the share of GDP accounted for by government spending have any relationship with the level or growth rate of GDP per capita?

This first figure shows the level of GDP per capita on the y-axis against the share of government spending in GDP on the x-axis. The idea is to see if there is any clear relationship between how “big” government is in terms of the economy and how rich countries are.

There isn’t much here the really stands out. For some countries, like China and Mexico, higher goverment shares appear associated with higher GDP per capita. But for others, like Japan, higher government shares seem associated with lower GDP per capita. But really, you can find almost anything you want in this figure.

We get a similar story if we look at the growth rate of GDP per capita (the 10-year average) against government spending as a share of GDP. In some areas you can tell yourself there is a positive relationship, and in others a negative one.

Rather than looking at government spending as a fraction of GDP, we could instead think about the tax rate. In this sense, maybe the important thing isn’t how much the government spends as a share of GDP, but how they finance it. High tax rates could influence incentives to save, innovate, or work.

This figure plots the top marginal tax rate in the U.S. from 1949 to the present. As you can see, the general pattern here is that this top marginal rate declines over time, with a few wiggles up and down. It is as high as 90% in the 1950s, and in the mid-30% range more recently. Just a reminder that this is the top marginal rate. So this is the rate paid on income over and above some high threshold. It is not the rate paid by someone earning minimum wage, for example.

For comparison, here is the lowest marginal tax rate, the rate paid on that minimum wage, for example. This rate is also slightly lower now than in the past.

In comparison to those two rates, what do we want to see? We want to see whether the growth rate of GDP per capita appears to be substantially different in periods with high tax rates and periods with low tax rates. The following figure plots a rolling 10-year growth rate for the U.S. (meaning that in 2000 it is plotting the annualized growth rate from 1990 to 2000).

Compare this to the figures on tax rates, and there isn’t any obvious connection. If anything, the period in which tax rates were higher experienced higher growth rates.

It is very important to note that these figures do not prove anything. They are simply allowing us to see if there are any really blatant correlations between government spending or tax rates and growth rates or levels. The fact that we don’t see anything blatant doesn’t mean taxation and government spending don’t matter, it just means that their relationship is muddy enough that it we can’t make it out from the raw data. One of the purposes of this section is to think about why this relationship could be so muddy.

Give and take

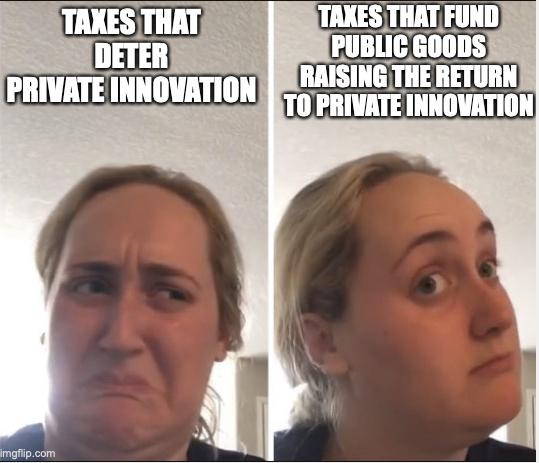

In evaluating the effect of government spending and taxation on growth, we have to be careful to account for both sets of consequences. That is, we have to not only look at what effect taxation has on the behavior of tax-payers, but we have to look at the effect of the use of those taxes by the government, and what they spend the money on.

To be concrete, think of adding some taxation into the Solow model. Say that the government levies a tax at the rate $\tau$ on all income. By definition, GDP is the total income earned by workers, capital owners, and those who earn economic profits (e.g. innovators, etc..) so the total income left for these people after taxes is $(1-\tau)Y$.

In the Solow model, there really is only one activity that people do, they spend a fraction $s_I$ of their income on capital goods, and the rest on consumption. So what this tax implies is that the total amount spent on capital goods is now $s_I (1-\tau) Y$, and not $s_I Y$. In the capital accumulation equation we used in the Solow model, that means the growth rate of capital is

\[g_K = \frac{(1-\tau)s_I}{K/Y} - \delta.\]Note that the higher the tax rate, the lower is $g_K$. Effectively, the tax is lowering the amount that people spend on new capital goods, which reduces the growth rate of the capital stock. If we stopped there, we could infer that the steady-state capital/output ratio would be lower in the long run. Remember that this was $(K/Y)^{\ast} = s_I/(\delta + g_A + g_L)$, so with the tax would be $(K/Y)^{\ast} = (1-\tau)s_I/(\delta + g_A + g_L)$. Lower steady-state capital/output ratio, lower level of GDP per capita in the long run due to taxes.

However, that initial analysis ignores what those taxes are spent on. Those taxes themselves might be used to supply capital goods such as roads, ports, and so on which otherwise would not be built by private industry. We cannot evaluate the long-run impact of the taxes without accounting for how they are used.

Here’s one example of how we could do that (but this is not the only way we could do this). Let the overall capital stock $K_t$ be a combination of both private capital goods (houses, factories, equipment) and public capital goods (roads, ports, schools). For our purposes, we’re going to just deal with them as if we can add them all up together (like they are substitutes) but we could do some more tedious math if we wanted to allow for the idea that they are not exact substitutes.

The accumulation equation for capital then needs to be modified from above. Let’s start over completely.

\[K_{t+1} = (1-\delta)K_t + I_{priv,t} + I_{pub,t}\]where we now have to take into account both private and public accumulation of new capital. Re-arranging this we can solve for

\[g_K = \frac{I_{priv,t}}{K_t} + \frac{I_{pub,t}}{K_t} - \delta.\]Private accumulation works as we said before, so that $I_{priv,t} = s_I (1-\tau)Y_t$, or private individuals/firms spend a fraction of GDP on private capital goods, and this is affected by the tax rate. What about the public side? Here, the taxes are spent on public capital goods, so $I_{pub,t} = \tau Y_t$. Put all of this together in the above equation

\[g_K = \frac{s_I (1-\tau)Y_t}{K_t} + \frac{\tau Y_t}{K_t} - \delta.\]Pull the capital/output ratios out of these first two terms and you get

\[g_K = \frac{s_I(1-\tau)+\tau}{K_t/Y_t} - \delta = \frac{s_I+(1-s_I)\tau}{K_t/Y_t} - \delta.\]Now look at this second expression. This tells us that a higher tax rate $\tau$ leads to faster growth in the capital stock. This is not surprising, in that we said the taxes are getting used to supply capital. But note how we’ve completely flipped the interpretation of the imposition of these taxes for long-run growth. Now, if $\tau$ goes up we get a higher level of GDP per capita in the long run. Because the government in this setting spends the taxes on capital goods, while individuals would only spend a fraction ($s_I$) of those taxes on capital goods, raising tax rates effectively increases the share of GDP allocated to capital.

This is not meant to be the model of how taxation and spending work. The point is that you have to consider how the taxes are used before making any determination of whether tax rates will lead to faster growth (transitional growth) or a different level of GDP per capita.

Think about a few alternatives, and you can easily come up with situations in which more government spending is associated with higher or lower GDP per capita, or where tax rates associated with higher or lower GDP per capita and growth.

Imagine, for example, that not all of the taxes collected are used for buying public capital. If only fraction $s_P$ of the taxes are spent on public capital, then the growth rate of capital will be

\[g_K = \frac{s_I(1-\tau)+s_P\tau}{K_t/Y_t} - \delta = \frac{s_I+(s_P-s_I)\tau}{K_t/Y_t} - \delta\]and whether $\tau$ positively or negatively affects the growth of the capital stock depends on whether $s_P$ is bigger or less than $s_I$. The point being that we have to know what taxation is used for before we make any conclusions about its effects. And for different countries, the size of $s_P$ and $s_I$ could be different, so that in one (Mexico?) higher taxes are associated with higher levels of GDP per capita, but for others (Japan?) higher taxes are associated with lower levels of GDP per capita.

But even then we’d have to keep considering what is donw with the taxes not spent on capital, the $(1-s_P) \tau Y_t$ in spending. Is that invested in human capital, through hiring teachers or providing health care? Or is it used for transfers, which then gets us into the question of whether we’re transferring money from people with low propensities to buy capital goods to those with high propensities.

Incentives to innovate

The prior section viewed the impact of taxes and government spending entirely as means of adjusting the capital stock. But we can easily imagine that tax policies and spending influence the innovation process as well.

Go back to the page on incentives to innovate and recall that we set up a relationship that equated the returns to innovation to the returns to work. In that setting we fudged a bit regarding timing of when those profits hit, and when the work occurs. We can update that to look like this:

\[\frac{s_{\pi} Y_{t+1}}{A_t}\frac{\Delta A_{t+1}}{R_t} = \frac{s_L Y_t}{L_t}.\]On the left are the profits per idea (which now depend on output in period $t+1$, after you’ve innovated) times the ideas-per-researcher, and on the right are the wages-per-worker. Now imagine that we’ve got a policy that levies a tax on economic profits from innovation at the rate $\tau$. This equation is now:

\[\frac{(1-\tau) s_{\pi} Y_{t+1}}{A_t}\frac{\Delta A_{t+1}}{R_t} = \frac{s_L Y_t}{L_t},\]and by itself we’d expect that this tax should lower the incentive to innovate. Why? Because you earn less money from each idea.

Re-arrange this relationship, and we can see how again the use of those taxes may change the story.

\[\frac{(1-\tau) s_{\pi} Y_{t+1}}{s_L Y_t}\frac{\Delta A_{t+1}}{A_t} = \frac{R_t}{L_t}.\]On the right-hand side is the ratio of researchers to workers, our measure of how much R&D is getting done, and this will determine the rate of innovation. The stuff on the left is describing the things driving this ratio. As we saw before, the size of $s_{\pi}$ and $s_L$ matters - the higher the profit share, the more innovation people want to do. And if we raise the tax rate, this lowers the ratio of $R_t/L_t$ for the obvious reasons.

What do the taxes get spent on? If they contribute in any way to an increase in GDP from $t$ to $t+1$, meaning that $Y_{t+1}/Y_t$ gets higher, then this can offset the negative direct effect of the taxes, and the ratio $R_t/L_t$ may not go down. It could even go up.

How would those taxes raise GDP into the next period? In the prior section we just saw one way: public capital goods. If those taxes are put towards spending on productive things like roads or schools, then GDP might be higher in the future, which means an innovators market is larger, which means more incentives to innovate. Improving the health or education of workers could raise $Y_{t+1}/Y_t$, if that increases their human capital.

A higher tax rate need not lower innovative activity if the use of those taxes is for activities that increase the size of the economy in the future. Innovators care about profits, and profits depend not only on the size of $s_{\pi}$ and $\tau$, but on the size of the market they get to sell into, $Y_{t+1}$. This is why firms want to sell in China, even though the effective tax rate due to their regulations and such is quite high, but very few firms want to open branches in New Zealand, even though their taxes are quite low.

The point again is not to prove that any specific policy is correct. The point is that you cannot evaluate any tax and spending policy without considering the effects of both sides. What effect does the taxation have on those taxed, and what effect does the spending financed by those taxes have on the economy? The muddy picture in the relationship of spending, taxation, and growth in the data is partly due to the fact that different countries do different things with taxation, some of which may contribute to growth, some of which may not.