Measuring fixed costs

We established that non-rival ideas about how to produce goods and services were crucial to generating growth in GDP per capita. And we established that coming up with those ideas, in the form of new products or firms or new procedures, required some fixed costs. This section shows some data on two types of fixed costs that one can consider: R&D spending and selling, general, and administrative costs of firms.

Increasing absolute research effort

The following figure shows the number of workers (or full-time equivalents) engaged in “research and development” activity. That could run anywhere from lab science for Chevron to market research for Nike. It also includes the activities of a lot of academics who work at universities.

For the most part, these numbers were increasing over time. Japan is something of an exception, although it is worth noting that Japan’s total population stopped growing in recent decades as well. The odd dip in the Chinese data is due to a change in reporting standards. Even leaving that aside, you can see that the US and China put more people to work in research and development than other countries. But while other countries are smaller, most appear to have increased the numbers engaged in research and development activity.

I plotted the absolute number for each country, as opposed to as a fraction of all workers, for a reason. We’ll in detail that productivity is different than any other kind of input (like laptops or bulldozers), and that the absolute effort involved is more relevant (instead of something like the capital/output ratio or the employee/population ratio).

We can instead look at the absolute amount of real R&D spending that was done by each country. Again, the absolute number is going to be relevant to us later, so that is what the following figure shows.

You can see that the US and China dominate in absolute spending now, but that this is due in large part to a massive increase in China over the last twenty years. In other countries, total spending on R&D rose as well, but in terms of scale no one matches the US and China.

These absolute numbers are useful, but it is hard to see the growth rates from this. Recall that we can look at the log of something over time to pick up on growth rates. The following figure shows the same information, only now with the log of R&D expenditures.

This maintains the pattern across countries in the amount of R&D spending, but you can see that the US, Japan, Germany, and the UK all had similar growth rates of R&D. China and South Korea both had very rapid growth rates of R&D spending. In China’s case, this allowed them to catch up to the US in total R&D spending, while South Korea caught up (almost) with Germany.

The general story here is that the absolute effort put towards research and development increased by a lot over time. For the US, from the early 1960s to today, total R&D spending went up by a factor of seven. The number of R&D workers tripled from the early 1980s to today. We (and most other developed countries) expend much more time and effort on R&D than we did in the past.

Can we see any impact of that? Below is a plot showing the number of patents granted by each country to applicants (whether they were residents or non-residents; lots of firms and people patent in multiple places). This isn’t a perfect measure of the total number of innovations being found around the world. Not all innovations get patented.

The absolute number of patents rose in line with the amount of R&D workers and R&D spending in these countries. The increased effort towards innovation does appear to be related to the number of innovations (to the extent that can be captured by patents).

But remember that productivity, $A$, is not a count of the number of innovations. It is more accurately a measure of how efficient we are at producing GDP given the rival inputs we use. And it is quite possible that an innovation could be produced that has very little impact on that efficiency. There are a lot of things that are innovative but have little economic impact.

If you’d like to amuse yourself, you can check out the examples in the video. You don’t have to get much past “toilet snorkel” to conclude that not every innovation necessarily improves productivity.

These are funny, but it is hard to believe that all of the increase in R&D spending and time was a complete waste. Those companies who engaged in it clearly thought it had some value, and we willing to pay these fixed costs in order to get something that they thought would create demand for a product or would lower their costs.

Firm cost structure

A different way of looking at the fixed costs associated with new innovations and entry is by looking at firm-level data on their costs. This isn’t comprehensive, but you can think of two distinct sets of costs incurred by firms that are reported on their income statements.

- Cost of goods sold (COGS). This is something like “production costs” and captures the costs of raw materials and other inputs that are transformed into the actual product the firm sells. The important part here is that these costs are very clearly linked to the quantity of product sold, $Q$.

- Selling, general, and administrative (SGA). These are fuzzier. Some of these might depend on $Q$, but many of these costs are fixed in the sense that they have to be incurred no matter how much is sold. Think of things like the accounting department, marketing, or legal.

The figure below shows you each of these costs relative to revenues for publicly listed firms from across the developed world, using data from Compustat. Because there are thousands of firms, the data is compressed into smaller bins defined by country, industry, and year. Meaning what you are looking at is something like the average of these ratios in for countries/industry/year groups.

The trends are kind of obvious. The ratio of COGS/Revenues declined over time across firms, meaning that less of their revenues were being accounted for by the costs of actual production. At the same time, the ratio of SGA/Revenues increased, indicating more of those activities. To the extent that we think SGA represents “fixed” costs associated with running firms, developing products, and expanding to new locations, then this indicates an increase in fixed costs. In that sense you could say that firms were spending a lot more on the fixed costs associated with developing those new products or expanding to new locations. This is similar to the increase in the R&D efforts we just documented.

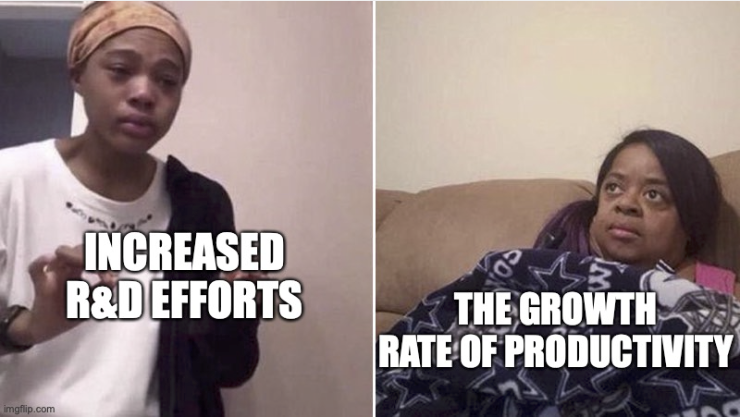

Effort and productivity growth

All this increased effort going towards fixed costs was not associated with a systematic increase in the growth rate of productivity, however.

The following figure plots the 10-year annualized growth rate of productivity ($(\ln A_{t} - \ln A_{t-10})/10$) for all these countries. You can see fluctuations, but in no case is there a sustained increase in the productivity growth rate. Even in China, which saw productivity growth rise to around 8% per year, has seen a steep decline in that rate over the last several years.

We already kind of knew this, because we know from the growth facts that growth rates in most developed countries are stable, and that the Solow model shows that these growth rates are driven by the productivity growth rate.

But this disconnect between the increased fixed costs and stable productivity growth rate is important enough to warrant a little label, as it is going to inform our work on modeling productivity growth.

The absolute number of workers and GDP spent on R&D has increased over time, and the ratio of fixed costs to revenues has increased at firms over time, but there is no systematic increase in the growth rate of productivity.

We can interpret this in terms of our toy model from earlier. There, we said that firms or new products enter until this condition is met,

\[f = \frac{s_{\pi}}{s_L} \theta \frac{L}{A}.\]and that productivity appeared to move in proportion to scale, which we saw if we just re-wrote this as

\[A = \frac{s_{\pi}}{s_L} \frac{\theta}{f} L\]This meant that productivity was proportional to $L$, and that productivity grew at around the same rate as population or scale. What we just saw in this data was that it looks like $f$ was going up for firms, at least the publicly traded ones or the ones doing formal R&D. That would suggest that there should have been a drag on productivity growth. If $f$ was going up, that should have lowered the growth rate of $A$.

One reason that may not have happened is that something else in this relationship could be changing too, and that is profits. We can use the same Compustat data to look at what happened to a very crude measure of the gross margin, which in accounting terms is Revenues minus COGS, divided by COGS. This isn’t accounting or economic profits, it’s just a crude measure of how much revenue firms have left after they have paid for the obvious cost of their products.

Because COGS/sales went down, it had to be that these gross profits went up, and they do. We can think of this margin in a slightly different way by thinking about the “markup” that firms change, which is the ratio of price to marginal cost. If the gross profit rate is going up then it makes sense that the price has to be higher than cost to some extent, but the “cost” of products isn’t obvious. COGS measures total spending on inputs, not the marginal cost of making another unit. Anyway, using a naive way of measuring this markup, here is what you get

The figure shows a clear increase in the markup. That’s true whether we just average markups across firms (Raw) or whether we weight the firms by their total sales (Weighted). If the markup was going up the same time that $f$ was going up, then this means that profits must have been going up, or $s_{\pi}$ was increasing.

The good news from that analysis is that it means if ideas or products are getting harder to implement or invent - $f$ is getting bigger - then that doesn’t have to mean that growth slows down. It does mean, though, that firms will probably earn higher profits to cover those fixed costs.