Competition and growth

Evidence on competition

The prior section explained that some profits are needed to stimulate innovation. What we will do here is establish that the relationship of innovation and profits is not as simple as “more profits, more innovation”.

To see what we’re trying to explain, the following is taken from a paper by Aghion, Bloom, Blundell, Griffith, and Howitt that looked at data from the UK to see how competition was related to innovation. They measure the “level of competition” using a formula like this

\[Competition = 1 - \frac{Rev - Costs}{Rev} = \frac{Costs}{Rev} = 1-s_{\pi}\]for each industry. The second fraction is the informative way to see their index. If costs are very close to total revenues, then profits (Revenue minus costs) are very close to zero, and this indicates the industry has a lot of competition. Either it is easy for new businesses to enter, driving down prices (and revenues) for existing competitors, or the existing businesses are selling similar products (HD TV’s) with similar features and hence no one can charge much more than cost. Either way, if the index approaches 1, then the industry is highly competitive.

On the other hand, if the industry is uncompetitive, then this is going to show up as one or more firms have high revenues relative to their costs - high profits - and hence the competition index of costs/revenue is going to be low.

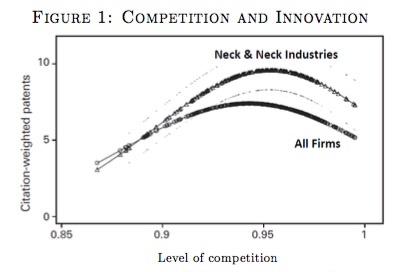

In the figure below, this competition index for industries is on the X-axis. On the Y-axis is a measure of how innovative each industry was. That is measured by using not just by how many patents were issued by each industry, but by how important those patents were. When a patent is really useful, it will get cited a lot by other patents. The index of innovation captures whether industries were creating important patents.

What you can see is a distinct hump-shape. When competition was low, innovation tended to be low. But it is also the case that when competition was very high, innovation tended to be low. Innovation seems to be maximized in industries that have medium amounts of competition. The authors further break down the results by whether industries are “neck-and-neck”, meaning the leading firms have very similar levels of productivity. In those industries, there is more innovation across the board, no matter how competitive the industry is to begin with.

We can put together some mathematical models of how this works, but that takes us pretty far astray into doing what is really industrial organization research on firm-level forms of competition and innovation. These models are at the cutting edge of modern economic growth research, but won’t add a lot to the basic intuition I’m about to describe.

So what is going on in this figure? Let’s think through three types of industries, and the incentives for innovation they have.

-

Very competitive industries: In these industries, the economic (and accounting) profits that a firm can earn are very low. It is either very easy for competitors to enter the industry or the product is a homogenous product. Think of gas stations. Even if a firm were to innovate, the profits available to it are very small to begin with, and it may be easy for all its competitors to copy its innovation. There may be little IP protection for innovations in these industries. Again, think of gas stations. They can try to tell you they’ve innovated (“Chevron with Techron!”) but let’s face it, it’s just gas. Firms in these industries don’t have a lot of incentive to spend time innovating, because why bother?

-

Very un-competitive industries: In these industries, there is a dominant player or perhaps a few firms that have colluded to divide up a market. They face almost no competition to their product. It may be because the costs of entry are huge either because of technical reasons (cable companies, airlines) or because of network effects (Google) or something like that. These firms also do not have a lot of incentive to innovate, because why bother? They already earn profits, and since no one can steal their business, providing their product more cheaply or at a higher quality doesn’t do them a whole lot of good.

-

Medium-competitive industries: These are in the sweet spot. The firms that produce in these industries are able to earn significant profits because they make something that is differentiated and valuable to people (Apple, Samsung?), but the presence of a competitor and/or new entrants means they cannot just sit around or they’ll lose market share. Each of the firms in these industries has to scramble all the time to innovate just to stay ahead of their competitors (or to keep up).

We didn’t prove anything formally here, but the intuition gives rise to this important point.

There is a medium level of competition among firms - neither perfect competition nor monopolies - that maximizes economic growth.

In economics we normally make a big deal about how perfect competition is the most efficient form of market organization. But note that this is a statement about the level of economic output given a level of productivity. If productivity were held constant, then we’d want all industries to be perfectly competitive, as that would maximize production. But if we’re thinking about growth in productivity, we don’t want perfect competition because this would limit innovation.

We don’t know precisely where the sweet spot is, and thus it is very possible that we have too little or too much competition in the economy to maximize growth, or that we are over or under-paying rival inputs relative to what would maximize growth. There is no clean answer to what economic conditions maximize innovation and economic growth.

Competition and the level of innovation

Let’s go back to our simple model of choosing $s_R$ from the prior section to think about how the findings in the above section work. This is just putting some extra math behind the words above.

We talked about the profits available to an entrant as

\[\Pi = pQ - cQ - F.\]That’s only a good description of entirely new firms or entrepreneurs, though, if you think about it. This equation doesn’t take into account the current profits a firm might be earning. Or if you like, it assumes that the firm we are talking about is earning zero profits to begin with. But what if they were earning positive profits already from some existing idea or product? Think of Apple deciding to introduce a new iPhone. A very important consideration for them is the fact that they will be cannibalizing the profits of their old phones when they introduce a new one. So we could instead think of the profits of firms (or anyone thinking of entering) as

\[\Pi_{New} = pQ - cQ - F - \pi_{Exist}\]where $\pi_{Exist}$ are the operating profits they would earn if they didn’t “enter” a new product and just kept selling the old one, and $\Pi$ are the profits they will earn if they replace their old product with a new one. Notice this makes it harder to justify a new idea or product. This is sometimes referred to as the Arrow replacement effect, which is the concept that firms don’t want to innovate to replace themselves. That is a waste of resources.

The entry condition on new profits upon entry is now that a firm/product/idea will get introduced if

\[F + \pi_{Exist} \leq s_{\pi} pQ\]which used the idea that $(p-c)Q = s_{\pi} pQ$ from earlier work. We can do lots of similar things to before. Say that $F = wf$ again. Assume again that $pQ = wL/s_L M = \theta wL /s_L A$. We’ve got

\[wf + \pi_{Exist} \leq \frac{s_{\pi}}{s_L}\theta w \frac{L}{A}.\]Now, what about $\pi_{Exist}$? That’s where the structure of the market’s comes in. We can say that

\[\pi_{Exist} = s^{Exist}_{\pi}pQ.\]To keep our lives very simple let’s presume that the $pQ$ revenues they could earn are equal to $\theta wL/s_L A$ just like the new product. The only difference in the products will be in their profit share they can earn. This means our entry condition is now

\[wf + s^{Exist}_{\pi}\theta w \frac{L}{A} \leq \frac{s_{\pi}}{s_L}\theta w \frac{L}{A}.\]We can cancel the value of $w$ and rearrange to get

\[f \leq \left(s_{\pi} - s^{Exist}_{\pi} \right) \theta \frac{L}{A}.\]This entry condition now says that it isn’t the profit share $s_{\pi}$ that matters, but rather the difference in the profit shares that the entrant could earn if they replace their existing product.

Now go back and think through the different types of industries again. In very competitive industries, the share of profits they actually can recoup is quite small, so for them $s_{\pi}$ is close to zero, and their existing profits $s^{Exist}_{\pi}$ are zero, so the entry condition is something like

\[f \leq \left(0- 0 \right) \theta \frac{L}{A} \approx 0,\]and there is really no reason to enter because at no point will fixed costs be less than zero. No one is earning as profits now, and no one can earn any profits if they innovate or introduce a new product. It might just be too easy to copy things, so why bother? Or the product we’re talking about it is just so plain and boring that no one really wants a new and updated kind no matter what. Very competitive doesn’t mean very dynamic, necessarily, it just means “close to zero profits can be earned”.

Flip over to the other end and a very un-competitive industry, which would be like one where a monopoly runs things. They do have high profits already, so $s^{Exist}{\pi}$ is big. And since they are the monopoly or something like it, they would also earn big $s{\pi}$ if they innovated. The problem is then that

\[s_{\pi} - s^{Exist}_{\pi} \approx 0\]and so the entry condition is

\[f \leq 0 \theta \frac{L}{A} \approx 0\]and again there is no reason to pay the positive fixed costs here to introduce a new product or idea. If you already have all the customers and earn high profits, why bother? This might be something like a local hospital group, airlines that dominate a local hub, or things like that. Little innovation because there is no threat.

Finally, the “medium” competitive industries have some firms that have positive zero current profits, $s^{Exist}_{\pi} \approx 0$ because they are behind the industry leaders. Adidas, maybe, hasn’t come up with a shoe to match Nike’s new model, or something like that. For those firms, if they innovate they can earn positive profits by taking over the leading position.

\[f \leq \left(s_{\pi} - 0 \right) \theta \frac{L}{A}\]is the entry condition and now this it is at least plausible that it is worth introducing the idea, because they aren’t sacrificing any current profits. When an industry has firms that are behind and that can earn profits from jumping ahead, they will innovate a lot to earn those positive profits.

What about the current leaders? They too have incentives to innovate in this case. If they do nothing, then they will lose their $s^{Exist}_{\pi}>0$ current profits. If they innovate and keep their leading position, they will lose $f$ dollars in fixed costs from innovating. The leading firm will still be willing to innovate so long as

\[f \leq s^{Exist}_{\pi}\]or they will lose less by innovating than by watching their competitors jump past them. Why would they be willing to lose any money? Because they know that they can always jump back ahead of the competitor in the future and earn positive profits again. We can be more sophisticated and presume that $s_{\pi} - s^{Exist}_{\pi} >0$ even for existing firms as if they innovate they can grab more of the market, and then it isn’t even necessary that innovating as a leader necessarily loses them money.

The larger point is that the most innovation comes from industries that have the a “just right” amount of competition that allows some profits to be earned (unlike perfect competition) but retains enough of a threat to those profits (unlike a monopoly) that they are scared into innovating. Figuring out what that “right” level of competition is through policy is very difficult, because industries differ and circumstances change. But we do know that having no restrictions on entry would be bad (too much hyper competition) but have too many restrictions on entry (allowing monopolies) is also the wrong move.