Modern demographic experience

What was clear from the sections on resources and growth was that the rate of population growth, $g_L$, mattered along the BGP. The faster population grew, the slower would be GDP per capita growth, as the resources were split up over more and more people. In a Malthusian world a positive association of $g_L$ with living standards leads to stagnation in living standards, even if it doesn’t imply collapse of them.

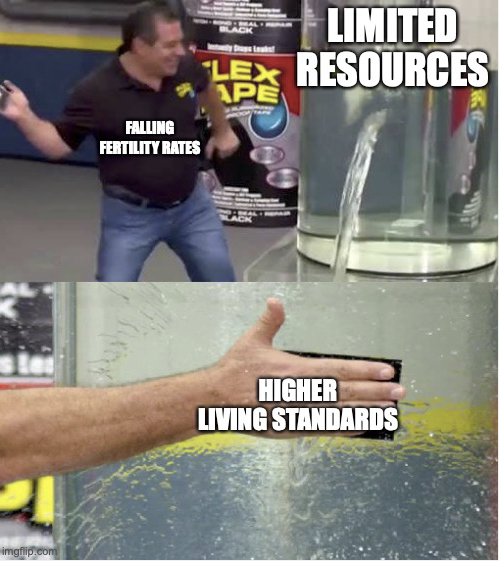

But does that Malthusian model do a good job of describing our modern economies? Should we expect that modern economic growth could come to an end because of population growth out-running resources? The answer is “probably no”.

The overwhelming finding here is that population growth tends to fall as countries become richer. You can look over long periods of time, and see that the number of births per 1000 people fell. From about 30 or 40 per 1000 people each year, to around 10 by 2010.

These long run data are only available for a few countries or subsets of people, but looking at a shorter time frame we can get a similar pattern. This next graph shows the number of children per woman, or the “total fertility rate”. This differs from births per person in how it measures fertility, but shows a similar story. The total fertility rate is a measure of how many children a woman born in a given year would have over the course of her life, based on the fertility rates of that birth year.

Around 1950 in Nigeria, for example, a woman born than year might expect to have 6 or more kids in her life. By 2015, that had declined to just under 6. But Nigeria appears to be an outlier compared to many other developed and emerging economies. In Ghana the fertility rate went from over 6 to around 4 kids per woman. In Bangladesh the fertility rate is now closer to 2 kids per woman, close to the low levels seen in most developed countries.

Beyond that, note that for a number of countries, like the UK, China, Japan, and South Korea the fertility rate is below two children per woman. That cutoff of 2 is critical. If every woman were to have 2 kids, the population would remain at constant size. But when fertility rates fall below 2 kids per woman, this indicates that $g_L$ is in fact negative. And we do see that in many developed countries the absolute population size has shrunk in the last few decades.

These time series patterns are useful, but do they really line up with the idea that the richer a country gets the lower the fertility rate? The short answer is yes. The total fertility rate (or children per woman) is negatively related to GDP per capita across countries. It appears that getting rich involves smaller families.

However, we have to be a little careful making conclusions that $g_L$ is necessarily negatively related to GDP per capita. The problem is that as GDP per capita gets higher, life expectancy goes up.

Even though people may have fewer kids, if they live longer then the population size may not fall as much as we think. Actually accounting for this gets a little tedious, but overall the drop in fertility is “winning” and it tends to be the case that as GDP per capita gets higher, population growth $g_L$ falls.

Model implications

What does this do to things in our models of growth? Well, there are a couple of things to look at. To make things concrete, let’s think about a world in which $g_L = 0$, as this appears to be where we are headed - at least!

In the Solow model, we know that the capital/output ratio is associated with $g_L$. $K/Y^{ss} = s_I/(g_A + g_L + \delta)$. If we set $g_L$ to zero, we get a higher capital/output ratio. So modern fertility works to make us richer. In our model of resources we had that the growth rate of GDP per capita depended on the population growth rate because it diluted resources, as in

\[g_y^{BGP} = \left(1 - \frac{\beta}{1-\alpha}\right)g_A - \frac{\beta}{1-\alpha}\left(s_X + g_L \right).\]If we make $g_L$ zero, this takes away one of the “drag” terms, and therefore the growth rate of GDP per captia gets higher. Again, modern demographics work in our favor.

What about with ideas? We know from that setup that the growth rate of productivity is itself

\[g_A = \frac{\lambda}{1-\phi}g_L.\]If $g_L = 0$ then this tells us that productivity growth stops. Worse, in our model with resource use, if we set $g_A$ to zero then the growth rate of GDP per capita could be negative (the $s_X$ term is still there).

Shutting down population growth would lead to stagnation in productivity growth, putting growth in living standards in jeopardy. Recall the example we used of Japan, where population growth has stagnated and so has the level of GDP per capita and productivity. One of the dangers of slower population growth is that it could stop living stanards from rising.

Perhaps that helps with some environmental outcomes. But recall as well that countries getting richer was associated with less pollution and lower resource use. If population growth stalls out productivity growth - or worse lowers living standards - then we might revert to more resource intense activities to keep up living standards.

Future fertility

Perhaps fertility might go up in the future? Accumulating evidence that maybe as incomes go up further so does willingness to have kids.